Film chosen and introduced by Devlin

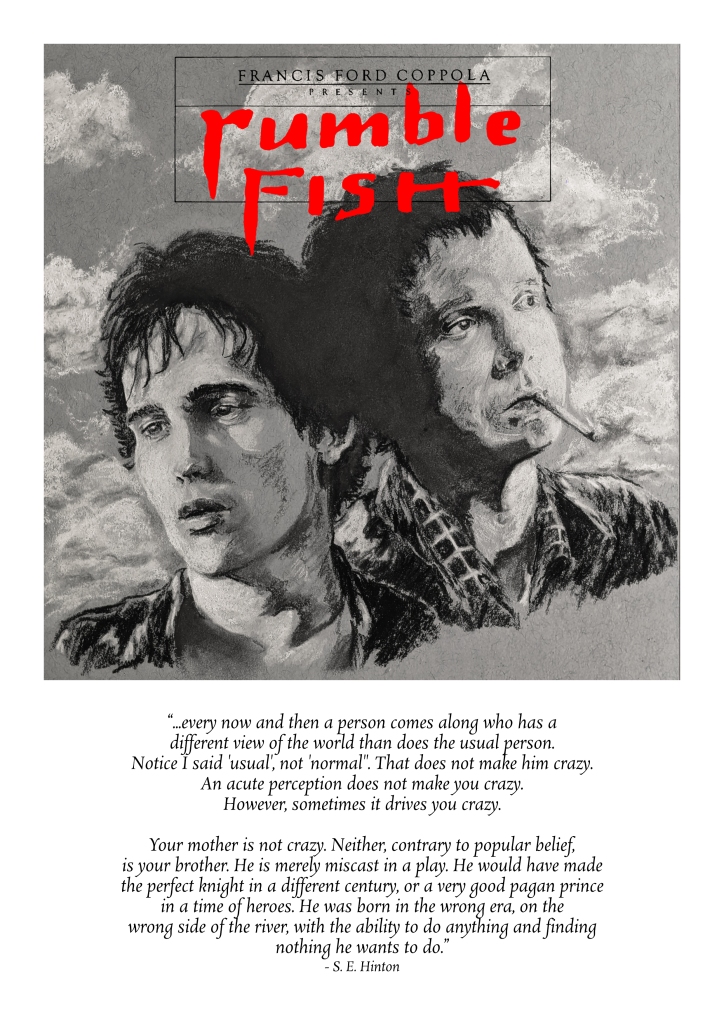

If you go across and check out the wonderful introductory graphics Matt created for our About section on this site, you’ll see that nestled in my alphabetically-assembled Top 10 Films list is this week’s pick – Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 teen dream Rumble Fish. That it took me 5 years to bring it to the team is the main surprise, as I’ve long been an evangelical admirer of it, surely boring Gali, Patrick and Matt many times over the years by droning on about my love of this odd little monochrome adolescent gang picture. Once I started dabbling in poster and shirt design, it was one of the very first films I decided to create an image for (SHAMLESS PLUG INCOMING – you can find giclee posters for this design on my Etsy store, and standard prints and shirts over at Teemill) as it has rarely been far from my thoughts.

Francis Ford Coppola was, I think, my 2nd movie obsession. I always credit Terry Gilliam for getting me interested in what a filmmaker was, what they did, how film could be a medium that, like visual art and music, could reflect the personality of the person making it, not just a quality product that entertains. Gilliam’s films are so identifiable, so concerned with his pet obsessions of the nobility of madness, the intermingling of dreams and reality, the absurdity of systems, and the lessons we can learn from archetypal myths. Coppola’s personality is not stamped into his films in quite the same unavoidable way, and his repeated themes and motifs are not mined with such regularity (although perhaps it is telling that this film, my favourite of his career, is the one that hews closest to Gilliam in terms of its oneirophrenic slipping between planes of reality, its mythical structure, and fish-eyed visual splendour), but his claim to auteurship is equally strong, despite the diversity of subject matter and formal presentation present in so many.

Coppola was at the forefront of what became known as the New Hollywood Cinema, the Movie Brats, those young interlopers that briefly managed to take over the asylum in the 1970s and harness the power of the studios to produce daring, grand, dense, personal and ambitious films to the widest possible audience. A graduate of the Roger Corman ‘school’, he earned his stripes re-editing and re-dubbing a Soviet sci-fi picture into the theatrically released B-feature Battle Beyond the Sun, subsequently persuading Corman to hand some leftover budget from the Ireland-shot feature The Young Racers, upon which he was the sound recordist, to craft a Gothic horror murder mystery called Dementia 13. Savvily doubling his meagre budget by pre-selling the international distribution rights, he dashed out a screenplay in 3 days and produced a feature that was solid enough to garner some positive notices and propel him a rung up the ladder in Hollywood. Warner Bros. released his UCLA thesis feature You’re a Big Boy Now, a satirical coming-of-age relationship comedy drama, in 1966, and Coppola was able to secure work as a writer on two more features that same year. His profile was sufficiently raised that he was tapped to direct a grand, yet awkward, old school musical in Finian’s Rainbow, whose star pairing of an aging Fred Astaire and the British variety show legend and pop music star Petula Clark is as good an indication as any to the bewildered state the mainstream Hollywood studios found themselves in as the Golden Age came to a grinding halt. While not a rousing success, he was able to parlay his experience to write and direct a fully self-generated feature, a prototypically late-60s philosophical road movie called The Rain People that would pair him with actors James Caan and Robert Duvall for the first time. Shot on location across various states with a small travelling crew that was augmented by local technicians, this sensitive, unabashedly intimate feature embodied a lot of what Coppola wanted from his career – the space and time to work on serious, introspective material with trusted collaborators. While not a hit, it offered an early glimpse to the kind of personal work that the coming generation would make their names with. Coppola envisioned a space, a safe haven for himself and likeminded creatives to flourish (most notably a young film student that had become his protégé, George Lucas) that he would call American Zoetrope, after the rudimentary moving-picture cylinder that pre-dates the invention of movie-making.

Coppola won a best screenplay Oscar for his work on the 1970 biopic Patton, which put him on the shortlist (or rather, longlist – he was behind Sergio Leone, Peter Bogdanovich, Peter Yates, Richard Brooks, Arthur Penn, Costa-Gavras and Otto Preminger) to adapt Mario Puzo’s mob novel The Godfather for flamboyant producer Robert Evans and Paramount Pictures. Initially turned off by what he saw as some tawdry sensationalism, his fledgling studio’s parlous financial status after absorbing debts from the production of Lucas’ debut feature THX-1138 and the middling reaction to his last two directorial efforts persuaded him otherwise. Still in his early 30s, Coppola of course went on to create one of the seminal works of American cinema – and capitalised quickly, releasing, over the next 3 years, the paranoid and remarkable The Conversation, and an even grander and possibly more lauded sequel in The Godfather Part II. Seemingly a made man, Coppola entered the mid-70s at the absolute top of the tree of movie directors. But his near-contemporary Martin Scorsese similarly graduated from Roger Corman’s stable to emerge as an important voice with his street-level gangster picture Mean Streets, capitalising quickly with the bleak and brilliant Taxi Driver. George Lucas captured mainstream acclaim with his nostalgic hangout picture American Graffiti, before throwing himself into the mammoth undertaking of creating his Star Wars universe. Brian De Palma, another Hollywood friend who transplanted from the East Coast, graduated from spiky, blackly comic satires like Hi, Mom! and Get to Know Your Rabbit, and future-cult classics like the psychological horror Sisters and mad rock opera Phantom of the Paradise, to the mainstream with his runaway hit adaptation of Stephen King’s Carrie in 1976. Relative youngster Steven Spielberg, a TV directing wunderkind, exploded to the forefront of the pack with his megahit Jaws. The industry moved quickly, cycling through other new voices whose fortunes rose and fell as quickly as the tides. While these contenders clawed for the industry’s attention, Coppola found himself deep in the mire of the film that would irreparably change the trajectory of his career, and mark out the literal and metaphorical end of a decade of remarkable directorial influence.

The brutal production of Apocalypse Now is well documented, not least by Coppola’s wife Eleanor’s on-set footage that was edited by George Hickenlooper and Fax Bahr into the lauded Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. Working from a script by John Milius that was intended for Lucas, the myriad catastrophes and acts of hubris that swallowed almost half a decade of Coppola’s career nevertheless resulted in yet another seminal feature – a truly transformative, hypnotic, chaotic, powerful indictment of the Vietnam War and the cult of militarism. Yet the director was left depleted – not least of all financially after having leveraged large amounts of his own capital to keep production rolling after the studios and the banks turned off the cash taps. He sought solace in what he hoped would be a very different kind of film. One that eschewed the bitterness and masculine brutality that haunted, in various forms, his three biggest hits to date. One that would allow him to engage his love of the shimmering spectacle of Hollywood’s Golden Age musicals in a way that he didn’t get to on the disappointing Finian’s Rainbow. One From the Heart.

The project was Initially planned as a stage-bound mini-spectacular that would harness the intentional, theatrical trickery of the musical movie form, but apply it to a story and a central romantic pairing that would feel more at home in one of the previous decade’s more familiarly human-scaled, working-class, naturalistic dramas. While a struggling young couple would bicker, fall out, make up, and circle each other in prosaic, everyday ways, the film would tell their story through songs, trick sets, intricate lighting cues, and, eventually a few dance numbers. Coppola’s ambition, however, just couldn’t be contained. Having decided to set the story in Las Vegas, the director set about building a simply extraordinary scale rendition of the city, replete with a glittering skyline of casinos, an airport and aircraft, thousands upon thousands of individually controllable lightbulbs, and neon signage so intricate that technicians had to invent a new method of blowing the glass and creating the electrical components. The budget more than doubled, and evermore complex funding sought to plug the gaps, resulting in a nightmare of overlapping vested interests looking for a return on their investments. Yet, all that money was yielding results – as well as the visual splendour the dailies were showing, Coppola was busy once again at the technical forefront of the medium. While the forced-perspective sets, painted fabric set walls that could be lit to be opaque or translucent, and magnificent swooping crane shots owed a debt to the film’s theatrical and cinematic forebears, his directing methods were entirely revolutionary. Often working from a huge silver trailer he dubbed the Electronic Cinema, he had access to instant feedback footage on video monitors. Tapes of rehearsals and takes could be quickly loaded onto machines to cut together dailies without having to rely on laboratories and the painstaking methods of flat-bed editing. Sequences could be pre-planned using material shot on videotape against a chroma key green screen, overlaid onto production stills or concept sketches.

In the end, though, for all these innovations, the audience for such a weird experiment simply wasn’t there. After the budget had ballooned to a staggering $26 million, much of it Coppola’s personal money and leveraged against his studio, the film took a truly catastrophic $636,796 internationally. A more chastening outcome could hardly have been envisioned. Perhaps there was a certain amount of comeuppance involved, as the brash, overreaching director finally stumbled. He had resolutely sought to distance the major studios as far as possible from his production, and couldn’t now expect much sympathy from them. Gone too was the guarantee that directors deserved the amount of freedom that they had enjoyed in the 10-15 years that preceded; while not on the same scale of disaster, Martin Scorsese’s King of Comedy was also an underwhelming flop on release in the same year as One From the Heart. Upstart director Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate two years earlier is widely credited as being such a financial catastrophe that it killed the New Hollywood era stone dead; I’d argue that this is a reductive reading, but combined with the fallow period several of the more high-minded movie artists endured in the first half of the decade, the party certainly seemed to be over – the commercially-savvy Spielberg the director who most benefitted while his associates floundered.

And it’s during this fallow period, more brutal than those of most of his contemporaries because of his uncertain personal monetary situation due to his aspirations towards creative autonomy, that Coppola sought to escape the inevitable blowback of the One From The Heart debacle by holing up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to adapt what American high school kids at the time would recognise as a classic of Young Adult literature – The Outsiders, a novel written by a teenaged S. E. Hinton about the intertwined lives of a group of unusually sensitive young gang members. Coppola had received a package of letters from some schoolchildren who asked him to direct an adaptation of the novel, and for the family-oriented director, the gesture proved touching enough that he felt moved to acquiesce. Assembling a cast of young actors that would, remarkably, provide the next decade and beyond with some of the most popular leading men and women in cinema (Patrick Swayze, Rob Lowe, Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez, Matt Dillon, Diane Lane, Ralph Macchio, C. Thomas Howell), Coppola finally found his footing as the director of a human-scaled project. Investing this romantic material with a suitably grand sweep, Coppola crafted a Gone with the Wind-inspired golden-hued bauble, a lush and nostalgic picture that ends on a plaintive note and an orchestral-backed, saccharine ballad performed by Stevie Wonder.

Coppola felt a sense of responsibility to the picture, to translate the novel in a way that would honour it in both narrative and form; to create a version that would bring what was at the time a syllabus staple in American schools to life for a generation of young viewers. Yet even as he was in the process of directing this feature, his restless imagination was already starting to chafe. He found another novel that S.E. Hinton had written, around a decade later in her life, that she herself described as somewhat angular, difficult, a book that few people really got. Rumble Fish.

Hinton was so guarded about this book that she didn’t even provide a copy to Coppola – he had to go out and buy one for himself. And, fortuitously, he did get it. He would chatter excitedly to Hinton about its use of symbolism, its classical structure woven from seemingly aimless asides, how readily he identified with the awe-struck younger brother Rusty James, who idolises his mysterious elder sibling The Motorcycle Boy. He and Hinton started crafting a screenplay quickly, in breaks during shooting or after hours, as Coppola sought out funding in an effort to remain at the production base in Tulsa and maintain momentum. Entire passages of dialogue were brought in almost entirely untouched, while Coppola set about using his revolutionary pre-visualisation technology alongside returning cinematographer Stephen H. Burum and production designer Dean Tavoularis to almost completely subvert the gorgeous magic hour sweep of The Outsiders’ visual palette with a harsh, contrast-filled, starkly monochromatic look.

You can listen for yourself to our discussion of the film – although it would be foolish of me to imply that I find it to be anything other than a masterpiece. But, sadly, it’s a matter of record that the box office haul for this strange little B-side to the decently popular The Outsiders was not significant. It did nothing to aid either Coppola’s money woes, nor his once-mighty status as one of Hollywood’s most powerful directors. His filmography for the remainder of the 1980s shows a man who remained busy, but no longer a creator whose films were capital-E Events. Seeking some sort of return to form, Coppola agreed to come aboard producer Robert Evans’ The Cotton Club in 1984– by this time a production that had already started to circulate in Hollywood as a debacle-in-waiting. The pair had clashed frequently while working together on The Godfather, but this was solid, familiar ground for him, adapting a 1930s-set epic crime-adjacent New York story from a draft already turned in by The Godfather author Mario Puzo. He was initially hired as a writer only, while Evans contemplated making the film his directorial debut after parting ways with his original collaborator Robert Altman in the wake of their misfiring Popeye in 1980. The project floundered for years as production funding was procured from a dizzying array of disreputable sources – arms dealers, casino magnates, and, allegedly, drug dealers, while Evans himself had to navigate a charge for cocaine trafficking before he could begin production in earnest.

When Coppola came on board, more than $10 million had already been sunk into a film that had yet to actually materialise anything of note. In contrast to the harmonious, nimble productions that he had completed in Tulsa the previous year, once again Coppola was at the eye of a financial and logistical firestorm, tasked with creating whole-cloth a lavish bygone era and balancing a huge cast of characters to tell the story of a jazz trumpeter who falls for a gangster’s moll in Harlem. Once again, excess became the key word. Co-writer William Kennedy talks of around 40 different scripts being turned out, most once production was already underway. A crew of over 600 toiled on vast sets, massive amounts of luxurious costumes, and complex musical numbers. Personnel turnover was enormous. The budget was blown through within weeks, leading Evans to dock Coppola’s directing fee, resulting in the director abandoning production until he received payment. Mobsters descended on the set to threaten Robert Evans due to the increasingly dangerous and murky deals he struck to find funding. Lawsuits and restraining orders flew in all directions. An eventual budget of $58 million, the most spent by any feature in 1984, all but guaranteed financial failure once again.

The film, nevertheless, garnered no small amount of acclaim – but also only half its budget back at the box office. Coppola also complained of creative constraints, most notably studio pressure to pare back the attention the final cut gave to the film’s black performers, despite the history of racial segregation and the unique challenges black artists faced in the face of it being integral themes in the film. Coppola would seek to right these injustices with a comprehensive re-edit, undertaken at his own expense, released in 2019 as The Cotton Club Encore.

Its positive notices and end-of-year-best-of list placements wilted in the face of yet another out-of-control, over-budget, underperforming debacle for a director whose on-set tribulations were fast overshadowing his products. His next move was to take on a lavish “4D” Disneyland attraction short film starring Michael Jackson, Captain EO, from a script by George Lucas. A curious, baroque, extended sci-fi music video, created for a performer who had harnessed the power of filmmakers better than perhaps any other during this decade (including the seminal 1983 John Landis-directed Thriller, and later in 1987 with Martin Scorsese’s Bad), there’s little to suggest that Coppola saw this as much more than a mercy job to pay the bills, provided by his long-time friend Lucas. Further solace was found in the for-hire gig of Peggy Sue Got Married, a cheerfully nostalgic high-concept romantic comedy, that opened to strong reviews, healthy ticket sales, and even Oscar nominations.

But this crowd-pleasing mini-streak petered out with the sombre military drama Gardens of Stone, a visually restrained, well-performed and quietly indignant return to the subject of the Vietnam War, this time from the perspective of a veteran who is stationed at an Army cemetery. Despite a strong return to the screen for lead actor James Caan, and a charming performance by Angelica Huston, the returns were minimal. But the disappointing lack of response for the film was, for Coppola, of no importance compare to the personal tragedy he suffered during production, when his son Gian-Carlo was killed in a boating accident at the age of 22. Griffin O’Neal, the 22-year-old son of Ryan O’Neal who was cast in the film, was driving, resulting in a messy legal situation and a heartbroken Coppola losing one of his children that he sought to keep so close – Gio had been an associate producer as far back as Rumble Fish, appearing in the film during the lake house party sequence.

Coppola dedicated his next feature to his son – 1988’s Tucker: The Man and His Dream. A long-term passion project detailing the life of innovative car designer Preston Tucker as he tries to revolutionise the industry in the face of opposition from the established manufacturers, the film began life as far back as 1973 before falling down his list of priorities and stalling out due to the fallout of the collapse of American Zoetrope after One from the Heart. While collaborating on Captain EO, George Lucas agreed to come aboard as Executive Producer, now flush with the massive success of both his Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises in as stark an illustration as any as to how the industry had changed across the decade. The one-time assistant, who broke through with a curious and cerebral experimental science fiction film under the tutelage of the ambitious, artistically-minded Coppola, now using the proceeds from his hugely successful, four-quadrant mainstream crowd-pleasers to prop up the ailing fortunes of a director who couldn’t secure funding by himself.

A handsomely-mounted, visually impressive, energetic film with a terrific lead performance from Jeff Bridges, it remains, sadly, one of Coppola’s most overlooked. Taking inspiration from, surprisingly, Paul Schrader’s gorgeous, experimental Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, which he produced, as well as classic Americana like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the picture radiates a joyful exuberance in the thrill of innovation, tempered by the chilling effect of vested interests and established orders that seek to derail those same innovations. Talk about life imitating art imitating life. Coppola later confessed that he hadn’t been able to produce a version of this story as good as he felt he could have, had he managed to begin production a few years earlier, before a run of brutal setbacks and tragic personal misfortunes. But I can’t help but think that the compounding effect of so much turmoil may have invested the film with a deeper sense of promise gone unfulfilled, ironically enough, creating a richer overall experience as the increasingly desperate Tucker tries to rally his troops with yet another frenzied singsong rendition of his ‘Hold That Tiger’ catchphrase. Coppola may have believed that he could no longer muster the gumption to embody the can-do spirit and grandiosity that he envisioned, but he produced a masterful, persuasive and rewarding film that deserves a reappraisal. Yet back in 1988, the film was most notable for once again ending up in the red, failing to recoup its $24 million budget.

In 1989, Coppola teamed up with long-time friend Martin Scorsese and contemporary Woody Allen for New York Stories, a triptych of short films set in their shared home city. Francis shared scripting credit with his daughter Sofia on a segment entitled Life Without Zoë. The film as a whole received decent reviews, but the Coppolas’ segment was often singled out as the weakest of the three – most praise being reserved for Scorsese’s Nick Nolte-starring Life Lessons, and the film remains more of a curiosity than an essential piece of cinema. Coppola would once again employ his daughter to unfortunate reviews the following year, as he returned to his defining work with The Godfather Part III.

The anticipation that accompanied his return to the Corleone saga must have been extraordinary, despite the straitened decade that had passed since Coppola’s last true hit. Already considered among the high points of American cinema, and having managed the unlikely feat of matching, or exceeding, the quality of the original film with his first sequel, the third installment had massive expectations to live up to – expectations that probably could never have been met. While the film did very good business off the back of the remarkable reputation of its predecessors, its reception was decidedly mixed in all sense of the word. Praise came for certain elements – the lived-in verisimilitude of how the previous 16 years might have treated the Corleone clan, how Michael’s actions will have weighed on him and his family, and the grand, tragic structure that emerges. The charged, complex dynamic between Al Pacino’s now-diminished Michael and Diane Keaton’s compromised Kay, on whom he so memorably shut the door in the chilling climax of the original film. The hot-headed performance of an emerging Andy Garcia as Sonny’s son, Vincent. But for other aspects, criticism – not least the performance of young Sofia Coppola as Michael’s daughter Mary, a victim, as the story goes, of a last minute pull-out by Winona Ryder. Untrained and out of her depth, she was the target of an inordinate amount of ridicule, a punchline for the best part of a decade until she proved her mettle as one of her generation’s more promising young directors. But mean-spirited guffawing at Sofia’s underpowered line readings masks further issues. A leaden, complex storyline that, while thematically interesting in its implication of the Catholic Church’s ties to organised crime, and mostly convincingly played, struggles to maintain momentum. A haphazard structure that confirms fears of an ill-planned venture being shaped on the hoof, rather than meticulously planned out. Not always a terrible thing for a creative, sharp filmmaker like Coppola, but in stark contrast to the rigour he brought to bear on the first film with his famous Godfather Notebook, a vast ring binder that contains virtually every page of the novel, broken down, annotated, interrogated for meaning, and restructured into a bible from which to create the most affecting, coherent movie possible.

The Godfather Part III, like so many of Coppola’s films, didn’t settle into its final form once the celluloid was loaded into the first projector on opening night. Coppola, like his friend George Lucas, is a tinkerer. A re-editor. A re-interpreter. The Godfather movies have been edited before, with Parts I & II edited together into a TV event miniseries in 1977. Part III was integrated into a video version called The Godfather Trilogy: 1901-1980. And more recently, Part III returned as The Godfather Coda in 2020. The changes made have allowed for a fairer reappraisal of the film as a worthy feature in its own right, albeit not entirely elevating it to the rarefied air of the first two movies. Coppola has, of course, remixed Apocalypse Now a number of times, most notably 2001’s Redux, a slower, somewhat bloated extravagance, and 2019’s corrective The Final Cut. Coppola also revisited The Outsiders with his The Complete Novel cut in 2005. It is, perhaps, telling that he has not seen it fit to make changes to Rumble Fish, despite opportunities when the film was reissued as a Special Edition DVD, and Criterion Collection Blu-ray, over the last few years.

Coppola’s stock had been raised by the lofty profile of The Godfather Part III, despite the less-then-stellar public reception. It was a visible mainstream hit, and at the very least, a media talking point. It also allowed him to take on another big studio production, one brought to him by a contrite Winona Ryder. In many ways Coppola’s last hurrah on the grandest scale, he brought out his entire bag of tricks for the lush, violent, genuinely strange Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Dubbed ‘Bonfire of the Vampires’, in reference to his friend Brian De Palma’s travails on 1990’s Tom Wolfe adaptation, and tagged early in production as yet another expensive catastrophe waiting to happen, Coppola defied the odds with a distinctive, truly influential Gothic horror hit. Parodied in The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror, making a genuine movie star out of Gary Oldman, inspiring a legion of would-be imitators (not least Kenneth Branagh’s sweaty Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), gifting the world with the ability to do impressions of Keanu Reeves’ English accent for years to come… the film was almost a phenomenon, and one that relied on, rather than tried to mask, Coppola’s gifts and talents. The beautiful sets, costumes, in-camera effects and overarching eye for theatricality, and the unavoidably weird eroticism stood out in an era that was becoming increasingly bloodless (so to speak).

Then he directed Jack.

Coppola bounced back, to an extent, with what, on the surface, maybe seems like a pale and anonymous movie for a man who had proved his abilities just 5 years before at the highest level with one of the most visually daring movies of his career. Arriving just a little too late at the tail end of the John Grisham legal thriller boom, his adaptation of The Rainmaker barely limped to a box office take that covered its production budget. As happened so often in the later years of Coppola’s career, a combination of poor luck and poor judgement on either his behalf, or the studios, left a genuinely good film to wither somewhat on the vine. Pairing Matt Damon, on the cusp of becoming a leading man with a rocket strapped to his back with Good Will Hunting just a few months later, with an ever-reliable, likeably sleazy Danny De Vito, and a post-Juliet Claire Danes, this would-be ‘one for them’ is as solidly entertaining a mid-90s legal drama as you could hope to find in the era. Featuring a David-vs-Goliath tale of Damon’s idealistic young lawyer representing a poor family trying to wrestle justice from a slimy insurance company personified in the loathsome visage of Jon Voight, learning to skirt the edges of legality while trying to hold onto his core values, and falling for an abused young wife, it’s a picture that boasts an abundance of personality and a stoutly constructed narrative. Its autumnal glow is expertly captured by cinematographer John Toll, and Elmer Bernstein’s warm, organ-driven score stands out from the standard churning strings the subgenre usually trucks in, setting an atmosphere of easy charm. Yet for all its positive reviews, name-recognition source material, and phenomenal cast, it made less money in its month of release than the abysmal Mortal Kombat: Annihilation. It’s final box office haul was less than that of Jack. Perhaps the market for Grisham material had finally been flooded? Or maybe the story’s stakes didn’t seem high enough? Had Coppola’s name become toxic? Or, was it just one of those inexplicable times where the general public just…didn’t fancy it?

By this time, the wounds were starting to add up. Coppola missed out on the late 90s and most of the 2000s to arbitrate a few troublesome lawsuits that bubbled under the surface – most notably a huge civil case concerning a botched adaptation of Pinocchio, another long-term passion project that was set to be his follow-up to Dracula. A contractual spat between Warner Bros. and Columbia Pictures saw Coppola win, then lose, $60 million in damages over the course of 6 long years. A bizarre re-editing job on a Walter Hill-directed, hugely over-budget James Spader-starring sci-fi movie called Supernova, done at the behest of MGM, could not help that project from floundering completely – in fact, his edit job was singled out as a horrible misfire.

At this time, his former running mates were seemingly working at full tilt – Lucas on his divisive but hugely profitable Star Wars prequels; Scorsese with the fascinating passion project Kundun, the eerie and affecting Bringing Out the Dead, and the grandiose epics Gangs of New York and The Aviator; Brian De Palma with the unlikely franchise-starter Mission: Impossible and the tacky but entertaining Snake Eyes (albeit stumbling with the bloated Mission to Mars and underperforming future-cult erotic thriller Femme Fatale); and Spielberg running a fascinating gamut from the slightly shaky one-two of megabucks sequel The Lost World: Jurassic Park and the stout historical drama Amistad, via the all-conquering World War II epic Saving Private Ryan, through the sci-fi inquisitions of A.I. Artificial Intelligence and Minority Report, the crowd-pleasing Catch Me If You Can and lesser follow-up The Terminal, the uneven but powerful War of the Worlds adaptation, and the challenging and murky Munich. How tragic that during this whole period, nobody could seem to find work for a director of Coppola’s calibre.

Coppola finally made good on a long-held ambition to work fully independently, and experimentally, after over a decade in which he eschewed (or was passively ejected from) Hollywood and filmmaking in order to build his wineries and resort real estate empires. His passion for both seem entirely authentic, but a man so completely soaked in cinema could never really walk away for good, and, with fortunes somewhat revived by astute business, he slipped off to a variety of European locales with a small crew for a completely self-financed passion project. His ‘comeback’ film, 2007’s Youth Without Youth, is a somewhat bewildering, time-hopping metaphysical fantasy romantic drama adapted from a Romanian novel. It’s about as far from the stout 90s workmanship of The Rainmaker as you could get, and it was met with a startling lack of fanfare. Those who even took notice that it existed, seemed to squirm uncomfortably in its presence and respond with reviews that ran from arms-length indulgence to derisive scorn. It is, for sure, a difficult film, and perhaps one that showed some ring rust. Coppola’s sense of story structure oscillated so wildly throughout his career – an award-winning screenwriter, lest we forget, who, when dialled in, was capable of some of the most precise and celebrated sequences in cinema, was also prone to throwing himself into chaos with only the barest hint of a road map.

Here, the chaos of studio deadlines has given way to an open-ended sense of curiosity, and the film certainly asks a lot of the viewer. Coppola slips into a densely layered story and feels his way through, employing a stickier and more maudlin approach to Rumble Fish’s themes of time running out, of the brutal briefness of youth, and how our lives’ span scarcely affords us the time to even scratch the surface of understanding it. Tim Roth plays an aging, suicidal linguistics professor on the eve of the onset of World War II, who is struck by lightning and starts to age backwards. He uses his regeneration to try to find the root of all human language in order to express the most sacred truths in the universe. He eludes Nazi spies and finds a doppelganger for his great lost love – a woman who also gets struck by lightning and starts cycling back in time through ancient languages. There’s…not really an easy way to dig through all this. Unlike Rumble Fish, the audience isn’t given much to hang onto. Performances skew towards the stilted and mannered, in contrast to the lusty, post-James Dean dichotomy embodied by Matt Dillon’s wounded bravado and Mickey Rourke’s preternaturally wise whispering. The dialogue, too, eschews the post-adolescent poesy of ‘glorious battles for the kingdom’, instead often burdened with impenetrable blocks of arcane academia.

Yet, as Scout Tafoya argues so persuasively in his ‘The Unloved’ video essay on the film, an artist as important as Coppola deserves a fair shake when they issue a work of art that is totally free of outside interference, that so completely harnesses their fixations and passions. I won’t try to argue that you’ll enjoy watching it – statistically, it’s very likely that most viewers will find it at least somewhat infuriating – but if you’ve come this far in reading about the life’s work of this most fascinating filmmaker, then I think you owe it to yourself to give it a try. At the very least, it seems to have worked as a youth serum for the director, who returned with two more features across the next few years with a renewed sense of inquisitiveness and innovation.

2009’s Tetro also has strong echoes of Rumble Fish – shot in black and white (with emotionally key sequences bursting into colour), it concerns an eager younger brother fascinated by a mercurial older sibling. It’s haunted by the failings of an intelligent but flawed father. It is set in Argentina, which, as noted in the documentary Locaciones: Buscando a Rusty James by the Chilean academic Alberto Fuguet, was one of several South American countries that seemed to respond to Rumble Fish a lot more favourably than their neighbour to the north. Perhaps the traditions of magic realism laid more of a foundation to appreciate Coppola’s frequent flights from the drudgery of reality into a space of symbolism and emotional, rather than ruggedly tangible, truth, than the more literal-minded North American artistic traditions. Reintroducing some of the emotional warmth that his earlier work trafficked in, via an open-faced young Alden Ehrenreich as Bennie, a teen cruise ship worker who heads to Buenos Aires to seek out his troubled writer brother Tetro, played with simmering tension by the talented and difficult Vincent Gallo, the film still aims for lofty themes and high-minded topics, but feels far more relatable on first viewing than Youth Without Youth. The febrile, close-quartered verbal jostling of the brothers, and Tetro’s sensuous relationship with lover Miranda, brings a physical heft that the earlier film tended to swerve, a reminder that Coppola can create rounded, multi-faceted human characters whose motivations can be nuanced and even contradictory, but still plausible and honest.

The extent to which this film should be read as autobiography is thrillingly shrouded. Is Coppola still the eager younger brother, chasing after a stand-in for the literate, cool August? Is he the blocked, thwarted Tetro, suffering under memories of the demands of a domineering musical maestro father, the cruel Carlo Tetrocini? Francis’ own father, Carmine, memorably composed several movie scores for him, and Coppola has himself reflected in interviews that he felt he couldn’t pull back on what he saw as some of the excesses on The Outsiders, for example. Or does he fear that he himself is Carlo, that his artistic achievements and single-minded determination have transformed him into a harsh taskmaster to whom his children may never live up? The film refuses to dole out easy answers, and while the gorgeous camerawork allows for a pleasurable viewing experience, Coppola and long-time editor and sound designer Walter Murch don’t make things entirely easy. Again, like Rumble Fish, the sound palette Coppola employs is often intended to unsettle, to reinforce the artifice of events. But the film contains more on-screen humanity than its predecessor, and the narrative, while still somewhat elliptical, is an easier follow. For me, at least, it was a revelatory first watch when I finally managed to get ahold of the DVD, a film which I joyously revelled in as a welcome return to many of the aspects of his work that I had previously enjoyed so much.

Tetro looked as if it would be a transitional film for Coppola, one that, after the heady, thorny Youth Without Youth, would allow him to balance his lofty aspirations with a more earthly, palatable presentation that would be a little more inviting to viewers. Certainly, it allowed for the most respectable praise he had received in many years, welcomed by some critics as a return to the kind of form they hadn’t seen from him since the 1980s, or perhaps even earlier, with The Conversation. But if we have gleaned nothing else from Coppola’s career to date, it’s that he seems almost wilfully resistant to garnering momentum.

He returned in 2011 with Twixt, a horror film of sorts shot largely on his own wine estates, starring Val Kilmer (once upon a time, an actor who withdrew from The Outsiders) as a hack writer drawn into an Edgar Allen Poe-fuelled vampire nightmare. After the lurid Gothic romance of Dracula, Coppola was back in the vicinity of the horror genre for the first time since Dementia 13 – this time, with an even more outré huckster zeal. Two 3D sequences were telegraphed with an on-screen graphic illustration of red-and-blue-lensed glasses, William Castle-style. Edgar Allen Poe himself pops up, played by once-and-forever agoraphobic surfing enthusiast and flatshare tyrant Matt from Game On (A.K.A respected character actor Ben Chaplin). Once again, colour and monochrome photography mingle to suggest meaning, albeit in less operatically emotive ways than in Tetro and Rumble Fish. What is jarring, though, is seeing a feature film directed by a filmmaker whose work often ranked among the most visually striking in the history of the medium that, even accounting for its hugely restrictive budget, looks like any number of cheap and cheerful films that you’d expect to see at a regional horror convention. Tetro and Youth Without Youth both made great efforts to disguise the 2000s-era digital cinematography that so many smaller projects of the era struggled to make look truly cinematic. Twixt almost seems to lean into the format, both in the prosaic real world segments, and the hyper stylised dream sequences that would appear to be Coppola’s impetus for making the movie.

Reviews were savage, commenting that the end result seemed almost amateurish in execution, and narratively rudderless when compared to the more thoughtful, revealing Tetro. That it remains his last completed work is fascinatingly enigmatic, if nothing else. It is definitely inessential when compared to the work that came before, and perhaps the most interesting way to watch the film is to try to fathom what about it seemed so vital to him that he felt moved to commit something so seemingly flimsy to film, given that he had just come off two very operatic, intellectually dense projects that radiated with the sense of ideas that he was in an incandescent rush to express. Perhaps a lack of anything burningly profound to say, in lieu of a somewhat in-jokey genre lark, is some sort of statement in itself? Or maybe this is just the work of a filmmaker who wanted to use his talents lightly for once, to steer himself away from the all-consuming and stretch his legs as some sort of curious exercise?

Fortunately (or perhaps foolishly – time will tell), it won’t be the last work of this storied career. Megalopolis has been Coppola’s great, lost project since the 1980s, a near-uncontrollably large scale film that seeks to explore fundamental questions of the human condition alongside utopian urban planning. Coppola’s 1990s trifecta of studio features were described as his attempts to dig his way out of debt and start work on the project. He continued during his ‘lost’ decade to try to get the work off the ground, amassing huge amounts of B-roll footage in New York that he had to discard in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. Casts of luminaries (Robert De Niro, Russell Crowe, James Gandolfini, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Paul Newman among them) would tentatively attach themselves, before stepping away as production never materialised. Yet, finally, almost unbelievably, the film does actually exist. Coppola has, once again, forked out his own fortune. Adam Driver (man of the hour for resurrecting near-mythical lost projects for troubled auteurs after taking the lead in Terry Gilliam’s long-delayed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote) heads up a remarkable cast including old friend Laurence Fishburne, and family members Jason Schwartzman and Talia Shire. Principal photography has wrapped, at an estimated cost of around $120 million, and fans, detractors, and curious onlookers alike await further news as to what, exactly, will emerge, when, and whether anyone will actually go and see it.

The film arrives at a parlous time for the industry. The flattening effect of bloated rosters of content across myriad proprietary platforms has rendered our shared idea of what constitutes a ‘film’ very unclear. Netflix originals derived from algorithmically-assisted dress-pattern scripts that synthesise current trends into passable material suck up the attention of landing page scrollers, who figure there to be little difference between these streaming-bound movies and their theatrically released counterparts. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson seems to appear in a new $150 million movie every 3-6 months that, had they just created a fake Photoshop poster to slap on the side of London busses and not bothered releasing the actual footage, nobody would likely have noticed. Studio IP still rules the roost, even as the wheels wobble on the once-unstoppable juggernaut of Marvel Studios, the Disney live-action reboot trend fails to gain any cultural traction, and the newly conglomerated Warner Bros. Discovery issues scattergun DC Comics adaptations in a dizzying array of non-canonical timelines. Coppola’s old compatriot Martin Scorsese finds himself cast at the centre of an exhausting, joyless ‘debate’ every few months, castigated by sulking adult babies for daring to point out that just because Ant-Man made them cry, that doesn’t make it high art, and that, perhaps, the medium that he has dedicated his adult life to contributing to as both an artist and a near-unparalleled curator and archivist deserves better. If this is how they treat the still-active and sprightly Scorsese, who can articulate his thoughts on the industry with some amount of compromise, how will this version of the industry receive the cantankerous, firebrand Coppola, coming off a run of bizarre self-funded features that the wider public don’t even know exist, as he brings a grand, mysterious, unapologetically highbrow and expensive original feature to the market? Can we envision any scenario wherein this doesn’t land with a disappointing thud? Think of Gilliam’s Don Quixote, eventually limping out into the world to a thin smile of commiserative pity from his remaining well-wishers, and a total lack of attention from the rest of the wider world. We do not live in romantic times.

That diplomacy with which Scorsese can tackle the industry has served him well, allowing him to continue producing top tier work into his ninth decade after suffering some of the same setbacks as Coppola. His 1980s saw The King of Comedy barely denting its production budget, and follow up After Hours similarly flying under the radar. Both have had their reputations thoroughly restored, with The King of Comedy especially becoming very influential, yet both were considered disappointments. The Color of Money is a well-directed piece, but perhaps more of a work-for-hire gig, albeit a very persuasive and successful one – which would have bought the director time and grace to continue with large scaled passion projects like The Last Temptation of Christ and, at the start of the next decade, Goodfellas, the movie that surely, permanently etched his name in the uppermost category of filmmakers and allowed him to tackle epic, personally-important projects to this day. Yet he still took on a studio remake of Cape Fear right after, partly out of gratitude for Universal Pictures’ support of the more difficult The Last Temptation of Christ a couple of years earlier. He was aware of his position in the system, and how to stay in its good graces.

Coppola, it could be argued, just couldn’t get along with the system to the same extent. He swung for the fences with One from the Heart and was never allowed to get back on an even keel. Rumble Fish, for me, is such a bittersweet joy because it feels like the most unencumbered he ever was, the film ending up as the most intense yet playful, deeply felt, unique work created by a Francis Ford Coppola at the peak of his powers – a man declaring ‘fuck it, we start shooting’ and going with his gut. The last of his chips were cashed in here, and while I’ve found much to love about films that came later in his career, he never quite managed to take that smart, or easy, way out that could have paved the road ahead a little more smoothly. Could the success of Peggy Sue Got Married have been his Color of Money, his Get Out of Director Jail Free Card, if he hadn’t immediately dropped the heavy Gardens of Stone to a fatal lack of reaction? Should he have held back on the unfashionable passion project Tucker: The Man and His Dream, foreseeing that an All-American tale of automobile derring-do would be out of step with a jaded late-80s audience who had already started to process that era only through the lens of irony? Should he have steered clear of a return to the world of The Godfather, avoiding side-by-side comparisons that would highlight perceived regression in his talents from that extraordinary early high water mark and make him seem past his prime? Did his Dracula have to be so fucking weird, given that it was supposed to be a cash-in job designed to get him out of debt and back to creating his own work? Could he have played nicer with the powers that be? In the end, though, it is surely this lack of compromise that gives his greatest films their fire. A Coppola who tries to play nice is a Coppola who ends up directing Jack. That he thought that he could just go ahead, 2 years removed from one of the single biggest financial fiascos in Hollywood history, and craft a black and white experimental teen gang picture with only one real fight in it, that revolves around a mumbly guy in a knitted tank top talking about fish, is, for me, just the most remarkable act of glorious artistic ambition. It’s not a flex, it’s not posturing, it’s a truly unique piece of honest creativity. There’s no one else quite like Coppola, and no film quite like Rumble Fish. We can only be glad that we have both.

Listen on Spotify

Listen on iTunes

Listen on Google Podcasts

Listen on Breaker

Listen on RadioPublic

Listen on CastBox

Listen on Stitcher

Listen on Overcast

Leave a comment