The Rewind Movie Podcast’s resident horror-heads, Devlin and Matt, return (from their graves) to trick and treat you to their one-stop Hallowe’en shop, as they curate another “All Hallows’ Evening.”

Join us for a seasonal slice of horror, art, and chat. It’s HalloRe’ewind ’25 aka HalloRe’ewind IV or V: Talkin’ Jive! The Rewind Movie Podcast’s HalloRe’ewind duelling triple bills! Two mini-marathons of 3-film blocks, as 6pm, 8pm, and 10pm screenings, so any old codgers out there can still get yourselves tucked up in bed by midnight!

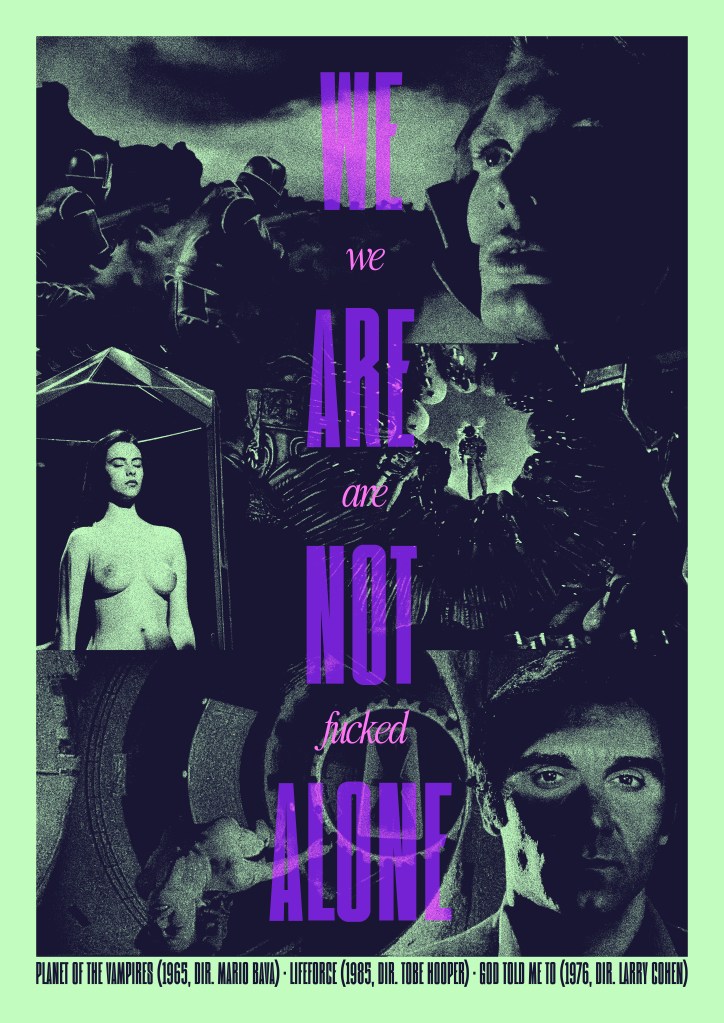

Devlin conjured up a We Are Not Alone, We Are Fucked trio, with three-courses of intergalactic terror. Meanwhile, Matt made Lycomania! his hirsutely fearsome threesome of hairy-handed, wolfy goings-on.

DEVLIN’S PICKS

During our HalloRe’ewind 2023 Double-Double Bill episode, Matt and I talked about the various flimsy tenets I set for myself about what I deemed to be important to a true “Halloween movie” that I’d feel like including in one of these seasonal marathons we find ourselves trading with each other. About how important it was to me that these films embodied a certain spirit, which would generally, ironically enough, involve spirits. Specifically, I was always keen on works that evoked that gloomy, misty, eerie feeling of a night where our ancestors braced themselves for the looming challenges of winter by seeking to commune with, placate, or ward off phantoms of old that took advantage of the thinning of the barrier twixt our world and theirs. My picks of course, did not stick to this hazy principle rigidly – a glance back at previous rosters makes that apparent – but as haphazardly as I applied it, there were films or themes that I just felt didn’t really work for me on Halloween. While I adore the Prince Charles Cinema in so many ways, their frequent 31st October programming of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre just never sat right with me. It’s fucked up, sure, brilliantly made, and leaves a bruise on the viewer, but it’s too earthy, too hot, too meaty to evoke the spectral weirdness needed for a good Halloween marathon.

But, it was, oddly enough, Chainsaw director Tobe Hooper who made this year’s theme absolutely undeniable, however incongruous it may seem. My central film for this 2025 triple bill was just too perfect not to talk about. And that 2023 quartet, themed around what I termed sludgy, slimy and sluggy GLOOP, wasn’t exactly prime ghostly territory anyway, and I thought those films worked well enough. There were also two films whose antagonists – intergalactic brain slugs and an insatiable pink gelatinous mass – descended from the cold void of space in which our fragile little orb is suspended. So for 2025, I felt it was okay to look not to the ethereal, but to the astronomical plane for our terrors, as we ponder various sinister invaders into our world. That’s right, They are Out There, and we are indeed, Fucked.

This year’s films still had to embody a number of completely arbitrary attributes that I demand before they could be included, to in some other way suit the unique feeling of hunkering down on a Halloween evening and engrossing myself in something that just feels right despite the radical change in location and genre. If I look back at previous marathons, I’ve deviated from more traditionally haunted fare in some of my choices, but could always connect them to a specific atmosphere I wanted to evoke. I think of Kurosawa Kyoshi’s Cure (キュア), a noirish contemporary mystery thriller of hypnotism and serial murder that takes place in a mostly grounded, but nonetheless eerie, Tokyo. Its lack of obvious supernatural content is offset by its off-kilter energy, its clinical detachment only deepens the viewer’s macabre curiosity in its sinister air. There are no gleefully gory caro syrup-soaked rubbery 1980s splatter effects, no pumpkins on porches, and no portrayals of ancient, soil-deep echoes and remnants of eldritch evils. It’s neither nostalgic camp, nor ghostly fable. But it is charged with something – a true, unsettling weirdness, which feels haunted in its own way.

It’s most often those two poles that define what I want from a Halloween movie night: the 80s flicks that somehow smell like rubber joke shop witch fingers, and the austere, truly unsettling films where it feels like something uncanny was physically captured by the camera and infused into the celluloid itself. That’s a high bar to reach, of course, and that’s definitely an oversimplification of a process that is more of an undefinable physiological reaction I feel seeing a film and getting the right vibe. My challenge, then, was, can outer space – primarily the purview of science fiction, however often that genre does cross-pollinate with horror – provide the right viewing experience for this most hallowed of evenings, as reliant as it is on the creepy rather than the cosmic? Science fiction primarily concerns, well, science – or at least heavily features technology – and doesn’t that imply a sterility or level of calculation and mechanical thinking? Isn’t that antithetical to my need for more unexplainable metaphysical magic?

Well, these three intergalactic horrors passed my illogical tests with flying colours, so here they are. As with any multi-film programme, you have to think about the flow, so let’s start with something nostalgic, stout, and stunning to look at. Something that feels like you could be watching while laying stomach-down on a sheepskin rug, chin cradled in your palms to peer upwards to a chunky, wood-panelled old TV that smelled of dust cooking on the tube, in some imagined, idealised early-80s suburban living room while you devour your trick-or-treat haul in a way you’ll definitely regret in a couple of hours from now.

6pm

Planet of the Vampires (1965), 88 mins

We open with the legendary Mario Bava’s Planet of the Vampires, probably better summarised by its original Italian title Terrore nello spazio, or Terror in Space, from 1965. Bava was a second-generation cameraman, following his special effects expert father Eugenio into the industry and carving a name for himself as a prolific cinematographer before stepping in as substitute director to complete Italy’s first sound-era horror movie I Vampiri.

His influence on the genre grew stronger still when he directed Barbara Steele in his full directorial debut La maschera del demonio, or Black Sunday, in 1960. A masterpiece of monochrome gothic horror, created as so many films in the Italian industry were those days as international-market cash-ins on successful industry trends that were shot with multinational casts to allow for regional dubbing, the film overcame a 7 year BBFC ban and numerous messy editing interventions by its US distributor American International to gain a reputation as one of the all-time greats. But in 1965, all this was in the future – the industrious director spent the early part of the decade expanding his gothic horror repertoire with the quality portmanteau I tre volti della paura (Black Sabbath), adding sword-and-sandalsploitation and Spaghetti Westerns, and most notably to helping create and codify the tropes and aesthetic of the giallo with La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much), and later the hugely influential 6 donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace).

The gorgeous, saturated colours and deep chiaroscuro lighting showcased in that feature are on full display in Planet of the Vampires, where stylish Roman streets are supplanted by a post-Jet Age, comic book fantasia of cavernous spacecraft and eerie deep-space landscapes. As Matt mentioned in our Rewind episode on Alien, the documentary Memory: The Origins of Alien features clips of this film as a clear influence on that masterpiece – even if Sir Wiggly Scott claims he’s never clapped eyes on it. It’s incredibly likely, however, that the more gleefully chaotic genre icon who penned the script, Dan O’Bannon (more of whom later!), had. I have no doubt that even a cursory glance at the plot would make it apparent how strong that influence was.

A crew, resplendent in piped black leather jumpsuits with incredible megacollars, pilot the grand deep space vessel the Argos (THE LAMINATED BOOK OF DREAMS!) towards a mysterious distress signal from a nearby planet. They contact their sister ship the Galliott on a video intercom, and decide to rendezvous on the surface. But their descent is interrupted by a near-catastrophic technical emergency, with only Captain Markary able to resist the incredible G-force. And, upon landing, he is the only person aboard who doesn’t wake up in a murderous rage, as the crew immediately start trying to strangle and twat each other into oblivion before Markary can shake them out of their violent fugue state. When they gather their composure, they attempt to hail the Galliott, but to no avail.

They embark on a journey across the planet’s foggy, craggy, bruise-coloured surface, dotted with smoking lava holes, to reach the stricken vessel, only to find a slew of corpses – including Captain Markary’s younger brother. A batch of bodies locked in the bridge mysteriously disappear while the Argos’ crew tries to free them, with the remainder being buried in strangely marked graves at the base of the ship. Returning to their own vessel to attempt repairs to the damage it too has sustained, the Argos now starts to lose crew members in mysterious circumstances. Markary intones a pessimistic outlook on ever getting the men and women under his command out of here alive into the ship’s log. And when one of them sees their deceased comrades rising up and walking around, their situation goes from dire, to dreadful. As the plot unfolds, we are clued into the fact that the film’s English title is incredibly misleading – there’s no vampirism to speak of, in the traditional blood-sucking sense, more of a parasitic entity, but in many ways that just ramps up the strangeness and paranoia that is woven into all the best celestial horrors. The invasion is as intimate as can be.

The film’s influence on Alien becomes even more pronounced when Markary leads a recon mission to another derelict craft that has been identified on this accursed planet – a ship whose exterior is littered with the fossilised remains of enormous creatures, vaguely humanoid but undoubtedly inhuman. Inside are more of these strange creatures, slumped over equipment that still functions. They were not the first to be called to this place by a mysterious signal…

The incredible strangeness, and awe, with which Bava depicts the crew reacting to this bizarre scene echoes that of the Nostromo’s crew’s infiltration of the crashed ship they too are beckoned to, which turns out to be their undoing. And while this production does not have the state-of-the-art visual talents of H.R. Giger, Ron Cobb, and Ridley Scott allied to the financial clout of a major Hollywood studio, the set is still impressive and weird – replacing the muted metallic shades of that film with sickly neon green and blood reds.

Similarly, in place of the naturalistic, overlapping, improvised-feeling interactions of Alien’s characters, our performances are rooted more in a traditional b-movie tradition of solid, theatrical blocking and line delivery. Yet this film’s pleasures, to me at least, are not ironic – that lack of naturalism becomes a virtue as the film retains an almost operatic sense of seriousness of purpose, in the face of its own potential silliness. It’s staginess lends a curious detachment that stunts any chuckles that may result from its somewhat threadbare nature, as miniature props which could read as adorable (okay, they still sort of do) and cavernous soundstage sets are aided by some beautiful lighting choices and a camera whose operator knows how and when to explore its spaces. Bava is able to evoke a genuine chill at times, his measured pace allowing the stark isolation to seep into the viewer, the dire circumstances of the crew to hang in the air around us and them. There’s such a sweet spot between the harmless charms of nostalgia and the genuine tingle to true menace, and this film, while sitting more on the nostalgic side of this equation, does manage to nail it.

It’s tight, clean, great looking, and reminds me of a superior episode of the original The Outer Limits TV series that began just a couple of years before this film’s release – right down to the requisite sting in the tail. And as posited, it seems to have inspired, at least partially, a young Dan O’Bannon to pen a feature about a ragtag crew answering a mysterious distress call. But this wasn’t O’Bannon’s only link to this tale of intergalactic vampirism, as the Return of the Living Dead and Blue Thunder maverick found himself taking a call from the infamous Cannon Films some time in the early 1980s…

Available on Blu-ray from Radiance Films

8pm

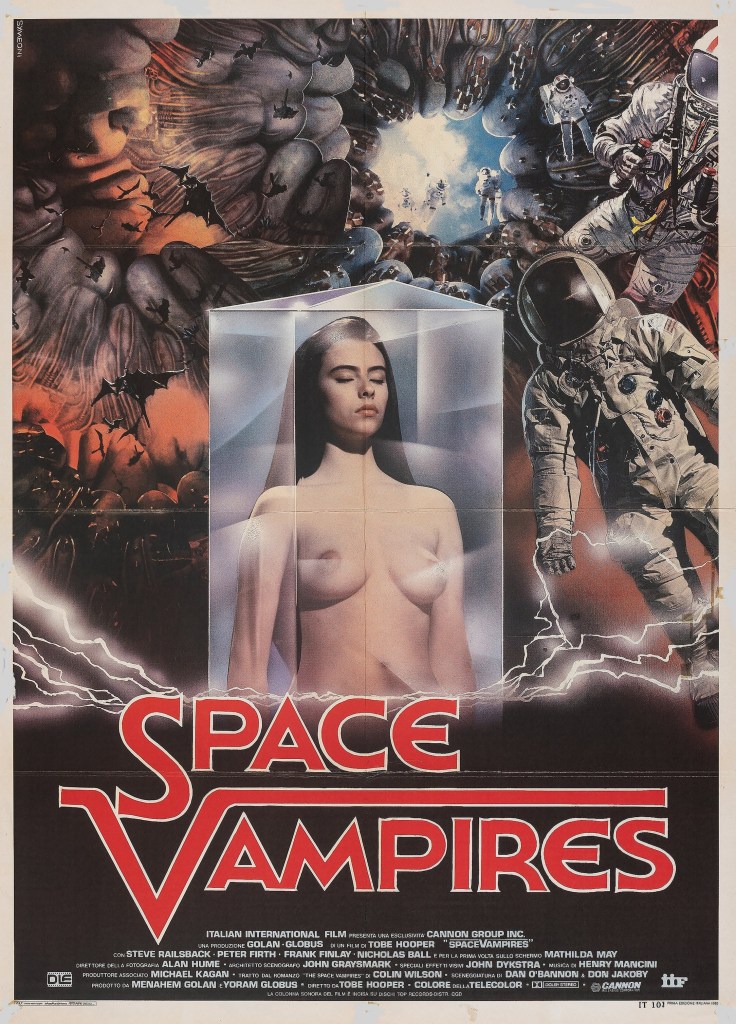

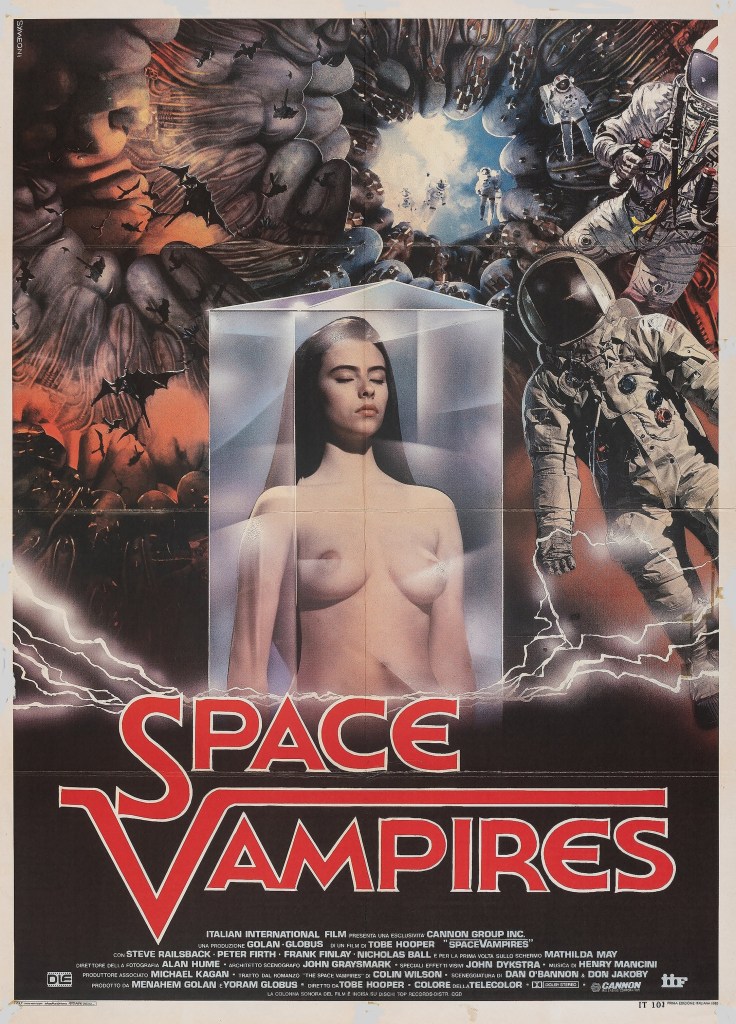

Lifeforce (1985), 116 minutes (International Cut)

Cannon head honchos Menahem Golan and Yoran Globus were running at full tilt at this time – with an enormous slate of various shades of exploitation pictures coming off the production line: cashing in on fads like the emerging hip hop/b-boy craze with Breakin’ and Rappin’, ninjas with American Ninja and the ridiculous Ninja III: The Domination, bawdy teen sex comedies such as Hot Chili and Hot Resort, and, most profitably, jingoistic and/or reactionary, violent action films like Missing in Action, Invasion U.S.A., and Death Wish II. But, for anyone who has seen Mark Hartley’s excellent Electric Boogaloo documentary, you’ll know that the company’s ambitions were not limited to chasing trends with cheaply produced shlock – Golan, especially, was a filmmaker who seemed to strive for some measure of artistic achievement, and it is in those ‘prestigious’ productions that some truly incredible, gonzo cinema can be found. The electric charge where high aspirations meet lowbrow instincts resulted in the likes of John and Bo Derek’s infamous, expensive globetrotting sex festival Bolero (a critically reviled flop), or Golan’s own high concept sci-fi musical The Apple (a cocaine-dusted disco disaster).

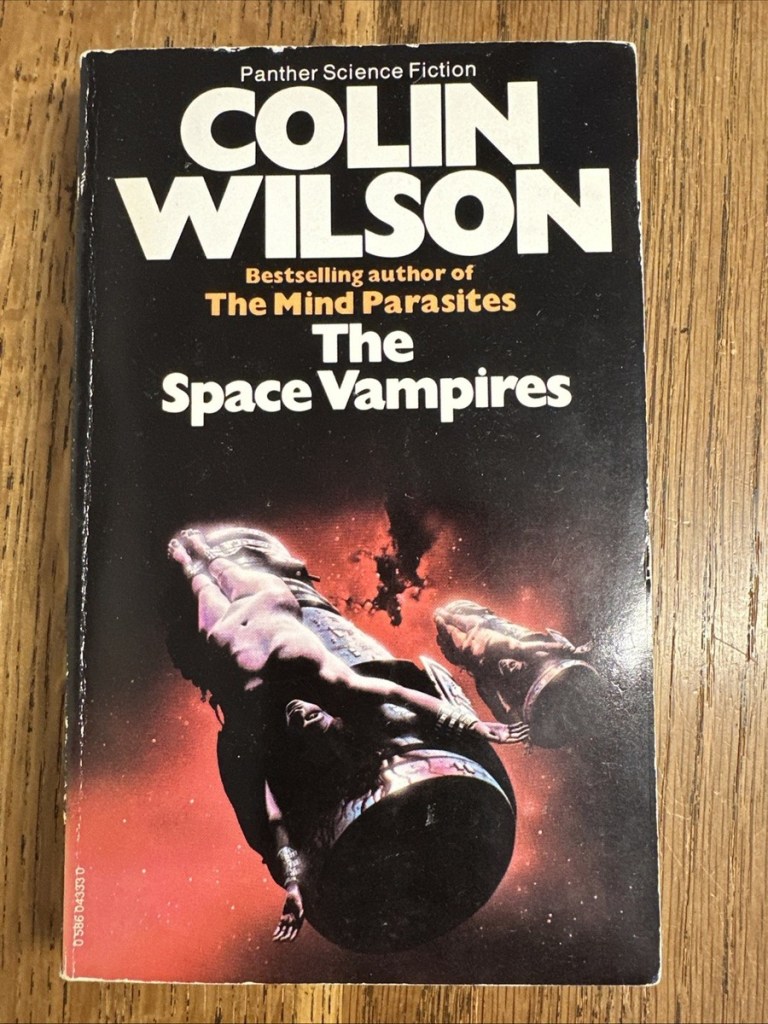

They also wanted in on the blockbuster game, signing legitimate movie stars to expensive contracts and funding glossy would-be A-pictures like Sylvester Stallone’s one-two punch of the parodically nasty cop thriller Cobra and the schmaltzy arm wrestling father-son bonding road picture Over The Top. These twin objectives were at play when Cannon snapped up Tobe Hooper, fresh from his huge success as director of Poltergeist (none of that Spielberg-really-directed-it conspiracy bollocks here, ta), and gave him a 3 picture deal, promises of hefty budgets and creative freedom, and a copy of Colin Wilson’s 1976 novel The Space Vampires.

Hooper tapped Dan O’Bannon and Don Jakoby to adapt the book – which, much like Planet of the Vampires, does not involve actual bloodsucking – making changes like bringing the time period back from the late 21st Century to the modern day, and smartly tying the plot to the impending rearrival of Halley’s Comet, which was due to pass by Earth in 1986 for its 76-yearly tour of scaring the locals. The screenplay retained Wilson’s very British take on Lovecraftian cosmic horror, however, and much of the basic structure, especially our initial set up.

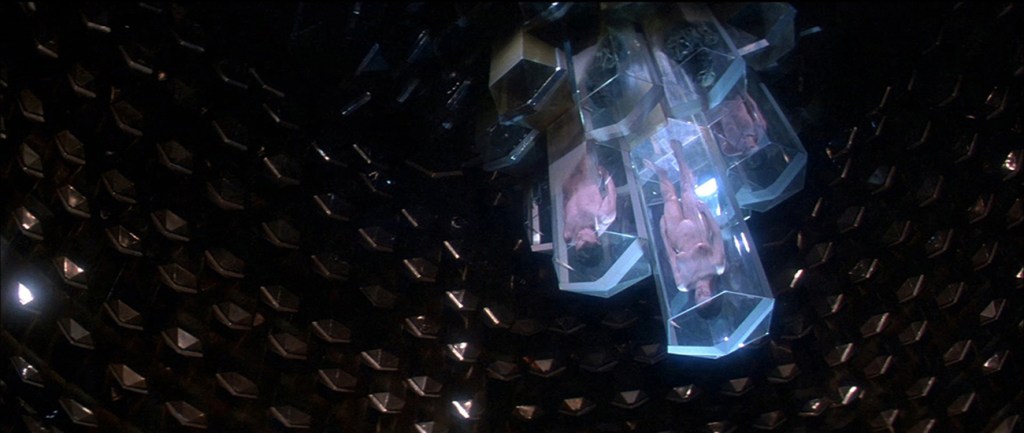

Opening on a grand outer space sequence, with a bold and blaring orchestral overture that is credited to the prolific Henry Mancini – who composed after first choice Bernard Hermann passed away right before he was due to begin work, took over from 2nd choice James Horner, and whose score was augmented during post-production by Michael Kamen, if you want to get a sense of some of the big hitters involved in this mad project – we see the Anglo-American crew of the space shuttle Churchill investigating what turns out to be a vast, mysterious, strangely shaped ship concealed in the tail of Halley’s Comet. Donning space suits and floating into an expansive, creepily organic passage within, the crew find the desiccated remains of huge, batlike creature, before a gleaming chamber of crystalline structures reveals the perfectly preserved bodies of what appear to be three young people – two men, and one woman – completely nude. The crew are immediately intoxicated by their presence, bringing them aboard the shuttle to travel home with them.

A time jump finds the shuttle now nearing orbit, but unresponsive and devoid of power. A rescue mission finds a burned-out interior, a dead crew, but the three humanoid creatures completely unharmed, bringing them back to a London research centre where they lay waiting for a scientific autopsy. When a horny young guard enters the containment room where the woman is laid, he instead finds himself being sucked dry in a blaze of colourful lighting when she surprises him by awakening and latching herself to him, draining him of his titular lifeforce. The base goes into high alert, but despite the assertion of science chief Dr. Hans Fallada that “a naked girl is not going to get out of this complex”, she of course does escape, killing a few poor saps along the way (including a security officer who seems to be trying to talk her down by offering her a biscuit, like she’s a rogue labrador) and stomping off into the darkness to wreak havoc.

Her mysterious male counterparts (one played by Mick Jagger’s younger brother Chris) also bust out in a hail of exploding glass and gunfire, while the base is distracted by the poor, seemingly dead, completely drained security guard violently rearing up during his own autopsy and sucking the life out of one of the doctors – suddenly restored to seeming good health but now a screaming hysterical wreck.

Into this mayhem comes SAS officer Col. Colin Caine (literally announced in front of a gang of assembled press corps as such, whom he asks to ‘strike that comment from the record’), a stuffy Home Secretary who promptly gets showered in corpse dust, and the strange reappearance of the only surviving astronaut from the Churchill, commanding officer Col. Tom Carlsen, who stowed away in the vessel’s escape pod as the situation became dire. At this point, we’re barely a third of the way into the film, to give you a sense of the maximalist onslaught this film gifts us.

Steve Railsback essays the haunted Carlsen with a mad Stanislavskian American intensity, while the majority of the British cast around him plum it up with their upper lips set as stiff as can be, and an arch eyebrow raised at the sheer audacity of the plot that lifts ideas from Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass stories and their Hammer adaptations through the 1950s, and brings them screaming into the excessive eighties with a truly impressive sense of subversion and strangeness – as happened so many of the great genre films of that decade that looked back 30 years, like The Fly, The Blob, The Thing, and Hooper’s own Invaders from Mars, his 2nd Cannon feature. Not content with naked intergalactic beings sucking the life out of people, Carlsen is revealed to have a telepathic link to the female alien, a gender-flipped reversal of the ubiquitous trope of the poor hypnotised woman under the thrall of the supernatural vampire. Here, it is Carlsen who devolves from stolid astronaut to a fevered, emotional basket case who cannot escape the erotic mental stranglehold placed on him by a beautiful woman-shaped monster.

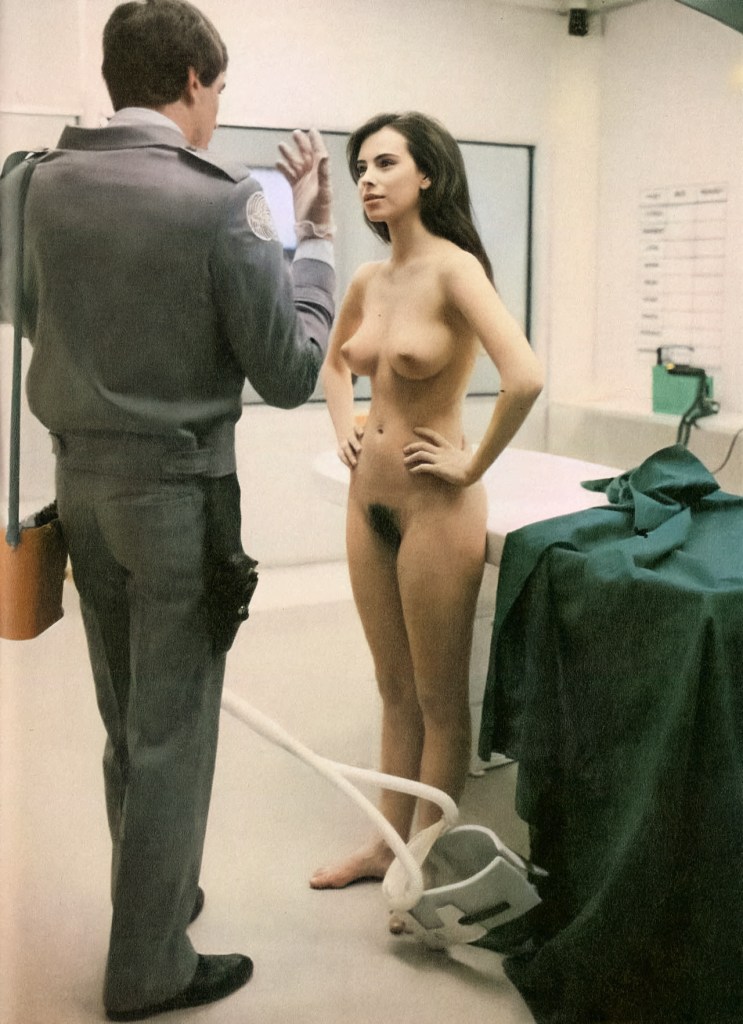

Which feels like the appropriate time to mention probably the most notorious aspect of this film – the almost entirely, graphically naked central performance by French dancer and actress Mathilda May. Sure, you can justify it in story terms if you feel so inclined. It does make sense – an alien race using basic human lust as the most obvious way to entice us towards our own demise. May plays the role with an incredible, otherworldly presence, sauntering through the scenes with fixed, intense eye contact and a hint of a confident smirk playing at the edges of her lips. It’s also pretty apparent that she is absolutely one of the most beautiful women ever committed to film, so Carlsen’s thrall to her is entirely understandable to the audience.

Hooper is a smart filmmaker, so all that was surely in the mix. But it’s also a pure provocation and a completely sensationalist point of difference from anything else in the market at that time – while cinema as a whole was pulling back from the sexual liberalism that accompanied the auteur-driven era of the 1970s towards a more neutered broad-appeal tone, Hooper comes out with a full frontal assault on the audience’s sensibilities in an expensive extravaganza mainstream feature. That Golan and Globus genuinely thought this could be a hit of the order of Alien was honestly fascinating – try and look at how many of the all-time box office top 50 rack up quite so many scenes depicting bare breasts (pun intended).

And make no mistake, this was intended to be a hit. The budget was $25 million – that’s significantly more than the aforementioned The Thing and The Fly, and in line with starry productions like The Untouchables. And it’s all there on the screen – not in big name actors, but in big shot creatives. Visual effects maestro John Dykstra, founding member of ILM, was on hand to bring to bear his experience on the likes of Star Wars and Star Trek: The Motion Picture among a team of experts in miniatures, opticals, matte paintings, animatronics… basically the whole playbook of the golden age of practical effects is wheeled out and executed to an incredibly high standard. And those gorgeous sets, prosthetics, models, and costumes were captured in stunning anamorphics by Return of the Jedi cinematographer Alan Hume. Who, okay, also shot a raft of Carry On… films, but surely his work on Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold balances out his cool points there. He was also an 80s Bond regular, so his ability to capture vast, innovative set pieces was unquestioned.

Those set pieces come thick and fast on our way to a truly balls-out, apocalyptic conclusion that could act as the dictionary definition of sticking the landing. The film’s genuine strangeness never dissipates, in fact, only evolves and deepens, the psychosexual obsession at its core investing every mad development with an icky complexity. Sometimes when audiences are confronted with something as odd as this, there’s a knee-jerk tendency to file it as camp – at which point, all that a viewer can do is determine to what extent the filmmaker is in on, or is the butt of, the joke, whatever that is. But to me, that is so limiting, as if wild ambition can only ever be a gag. Don’t get me wrong, this film is fun as hell to watch. Many lines of dialogue are incongruous, or flat out hilarious. The stiffness of the many grey Brits in the face of this supernatural onslaught is an absurd juxtaposition. But I feel like those elements are all sharpening each other in a way that achieves what any film should aspire to achieve – being undeniably entertaining. It’s an intentional clash of styles and content, the eerie and unsettling subtext of mid-Century cinematic horror turned gaudy, all-caps supertext with gigantic animatronic bat creatures and exquisite breasts.

That entertainment is just perfect for a Halloween night, too. While it is a cosmic sci-fi horror, it takes so much from the lurid atmosphere of vintage Hammer Studios – tying the phenomenon to the lineage of traditional vampire lore in explicit terms, sinister women in billowy nightgowns, men in heavy tweed suits discussing What Must Be Done, even a big gothic cathedral showdown. And there’s a co-mingling of the intergalactic sci-fi themes with the metaphysical, as the visitors shapeshift to embody our base sexual desires, and use that to feed on human souls – opening questions about what, exactly, is the essence of a being.

It’s all so magnificently well made, and all so admirably unconcerned with restraint or so-called good taste. But it also means what it is doing. It’s a talented madman, abetted by other talented madmen, with fascinatingly specific interests, ready access to genius technicians, and a fat stack of money (and all the high grade cocaine that can be purchased with it), knocking it out of the park. To really get the best of this, I heartily recommend you meet it head on and wallow in its weirdness. It played like gangbusters at a recent screening at London’s newest, truly wonderful little grindhouse cinema The Nickel.

Available on Blu-ray and 4K from Arrow Films

T-shirt and poster prints available at Teemill!

10pm

God Told Me To (1976), 91 mins

As mentioned at the top, every good movie marathon needs a flow. I wanted to consider the era – we’ve been to the mid-60s, and the mid-80s, and I wanted to ensure that there would be balance with the remaining pick. Rather than look even further back to the 1950s (a heyday of emerging science fiction films, but many of which are quite staid), or onwards to the 90s and beyond (where true gems can tend to be harder to find among the sheer glut of available material and the co-opting of genre tropes right into the mainstream), I’ve split the difference in the 1970s. Specifically, the grimy, dangerous New York streets of the 1970s, in the thick of the grindhouse era.

Just as the operatic craziness and expensively assembled effects of Lifeforce made for a welcome change of pace from the stagebound and sparse Planet of the Vampires, a different vibe was needed, as there really is no topping Lifeforce for grandiosity. Instead, I wanted to finish the evening on a minor key, a hanging note designed to get under your skin and keep you staring at the ceiling long after you’ve turned the bedroom lights off (if you dare).

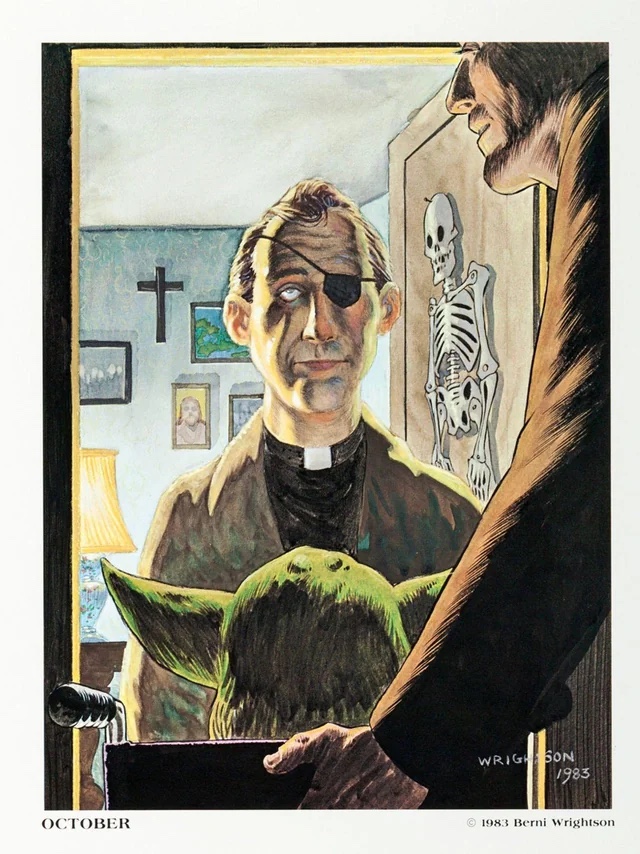

Carrying over the thread from Lifeforce of the intersection between science fiction and religious ideas of the existence of a soul, or essence, is “King” Larry Cohen’s 1976 psychotronic thriller God Told Me To, the fifth feature directed by this icon of independent horror. Cohen’s early career as a writer of TV procedurals – including 3 Columbos – informs his approach to the story of guilt-ridden Catholic street cop Lt. Peter Nicholas, played with an understated authenticity by Tony Lo Bianco, who is pulled into a mysterious conspiracy after he arrives on the scene of a violent killing spree.

A man stands atop a water tower gunning down over a dozen total strangers in the street in broad daylight – an act of ordinary brutality in a violent society. Nicholas risks his life to climb up to speak with him, sharing details about himself in an effort to connect, and finds the young man exuding an ecstatic calm. When he asks him why he did it, he simply states “God told me to”, before leaping to his death.

More murders happen – a knife spree in a supermarket; a New York City cop (played by Andy Kaufman) guns down several fellow officers and bystanders in the middle of the packed St. Patrick’s Day Parade; a father coldly relays to Nicholas how he murdered his wife and children in horrible detail. Each time, Nicholas hears those same words: “God told me to”.

He hears the mother of the rooftop gunman speak about a new acquaintance of her son’s in the days before the killings – a long-haired young man by the name of Bernard Phillips. He corroborates with witnesses of the other crimes, asking whether he had been seen with any of the other assailants before they acted. He was – but beyond a vague idea, none of them can ever recall any details about his face – no features, no specifics. Just a ‘hippie type’. But it’s enough for Nicholas to track down who he believes to be Phillips’ mother – a woman who, as soon as Nicholas appears at her building to ask her some questions, maniacally attacks him with a knife in the stairwell in a scene which exemplifies Cohen’s run-and-gun shooting style, where available light, handheld cameras, and practical locations (usually with limited permits) heighten the mayhem with a sense of verisimilitudinous danger.

When the woman falls to her death on the stairwell in the melee, Nicholas uses Police records to track down a now-elderly man who encountered her some 25 years before – running naked through a near-deserted area in the middle of the night. He relays the story of how she claimed to have just been abducted from the beach by some unseen force, and taken aboard a craft of some kind, where they implanted a child in her. The doctor who delivered Bernard Phillips corroborates her assertion that, despite having given birth to a child, she was a virgin.

Nicholas becomes increasingly invested, with his private life suffering – his new girlfriend feels neglected by both his fixation on the case, and his intense relationship with his estranged wife whom he is in the process of divorcing, complicated by his Catholic faith. He decides to defy his superiors by releasing details of the various assailants’ stated religious motivation for their killings, sparking a minor wave of hysteria across the city that bleeds into real world consequences, as a street hustler murders his corrupt NYPD contact and disguises it as one of the ‘God’ murders. Watching the affable, responsible Nicholas fray at the edges pulls the viewer into the deepening madness of the story, as the matter-of-fact presentation establishes a baseline normality and tangibility, which is exploded when a shadowy cabal of wealthy fanatical followers of this new God finally lead Nicholas to Bernard Phillips.

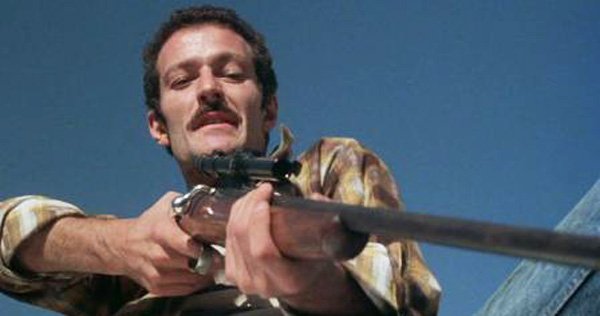

Richard Lynch so often embodied oddness on screen – filmmakers often using his physical scarring as shorthand for sinister intent in an unfortunate trope that continues to this day – but here, bathed constantly in a sickly orange light that bleaches out his features as he floats around the scene like a curious bird, he really does read as some otherworldly menace. His appearance marks the turning point where the story’s religious and supernatural madness seeps into the film itself, where a violent, retributive God may actually be a celestial traveller with passive ill intent, and intergalactic messiahs litter society, some skulking in cramped basements puppeteering ordinary people into committing horrific acts of violence for ineffable purposes.

The Catholic Church, the Police, society itself is fragile and sick. The universe is wide and scary. We know so little, and understand even less. The terror of realisation, of our infinitesimal smallness in the face of a vast and indifferent cosmos which may contain threats so horrific that even contemplating them would be enough to drive us to madness feels like it is a deep-seated part of us all. Religion, folk tales of spirits, abductions by little green men – are these stories we tell ourselves to make sense of the ineffible mayhem? That a system of transgression and fair punishment, of a soul-ledger that pays out in some promised afterlife, is a cheap plaster-cast stucco wall designed to draw our eyes away from the horrors that we’d be forced to reckon with if we just cast our gaze over its crest at the pregnant blankness above? What if God was one of us? What if God was angry at us? What if God didn’t give a fuck what happened to us? What if any of these theories was more psychologically tolerable than the insanity-inducing truth that we are simply not equipped to contemplate?

That’s what drew me to this concept, and what informed all three picks, as different as their approach was: that the ultimate source of spectres and ghosts, spirits, echoes of the past, gods and monsters, and the mysteries of the shiny discs hurtling through the galaxy towards us from distant planets, is our own overactive brains, dwarfed a trillion times over by a vast, expanding, uncaring universe. Planet of the Vampires preys on the human instinct to explore, and to assist. Lifeforce adds to that mix the brain-fogging effects of basic human lust as an achilles heel. And God Told Me To confronts the moment the monolithic narratives we’ve mapped onto our lives to impose some basic sense of order give way when we glimpse the void beyond. Our instincts to explore, our fascination with what’s just over the horizon, is met with the horror of what we might find there.

And what could be scarier than truths we can’t bear to face?

Available on 4K from Blue Underground

MATT’S PICKS

“Haven’t you heard? Last night… six of ’em. All in different parts of the city, all mutilated. He must be a real right maniac, this fella.”

Taxi Driver, An American Werewolf in London

We’re all well aware of werewolves. The Korean kids I teach know all about them. Howling, shapeshifting transformations from human to beast under a full moon, and silver; especially silver bullets, are the weapon of choice. Yet it’s a peripheral, but inherently cinematic monster, with iconic early classic creature codifiers Werewolf of London and The Wolf Man, and their wolfish cinematic children being the cornerstones of our lycanthropic awareness. In spite of folklore and legend being abundant, this mad monster lacks an overarching formative text like a Bram Stoker’s Dracula from 1897, or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus from 1818. Although not quite as overexposed as its creature contemporaries—and arguably now as completely saturated and telegraphed as the zombie film, with its own prolific, periodic resurgences, one could argue werewolf movies are equally as compelling and evocative as a horror subgenre.

The burden of lycanthropy brings with it sadness, pity, and pain—not quite our Hallore’ewind tempo. However, I sought out some cackles and howls to help sweeten the disturbing body horror of it all, and to balance the occult books a bit. So grab a copy of Warlocks, Werewolves, and Demons from Dick Miller’s bookshop—it’s about to get hairy. For starters, the uncanny lupine year of 1981 heralded an unexplored—and to this day, unbeaten 12 months of (sort of) werewolfery. Consider the following furry films each emerged within ’81! The Howling, Night of the Werewolf aka The Return of the Wolfman aka The Craving, Wolfen, Full Moon High, and An American Werewolf in London.

Fascinatingly, a lycanthrope is typically a brutal villain, yet innately evokes sympathy, as an individual cursed with werewolfism is frequently both victim, witness, and monster combined. Within the constraints and restrictions of werewolf cinema lurk a rich and diverse number of allegorical manifestations over the last 90 years or so, beginning with Werewolf of London in 1935. Craig Ian Mann’s Phases of the Moon: A Cultural History of the Werewolf Film goes to great efforts to gripe with the admittedly all too simplistic singular theme of a Jekyll and Hyde-esque duality of the self, and the awakening of a dormant beast within. It’s evident that a multitude of meanings populate lycanthropic depictions on film, often capturing a zeitgeisty snapshot of concurrent historical and political events to express the fears and anxieties of the times.

Deep breath: themes of alienation, sexuality, mania and madness, puberty, oppression, depression, anti-establishment rebellion, depraved or suppressed sexuality and deviancy, disability, substance abuse, homosexuality—and its inner struggles, an inheritance of damaging paternal traits, a device to explore constantly changing depictions of masculinity—and to a lesser degree femininity, the Nazi Third Reich, a Pagan threat to Christianity, indictments of conservative values, digs at Reaganomics, repressed male aggression, power, and identity, the afflicted reconciling with their internal monstrosities and turmoil, the lunar cycle as a menstruation metaphor, the church’s patriarchal control, burgeoning adolescent males with hairy hands leading to masturbatory inferences, being allegorical of serial killers, race, class, and gender politics, the social underclass, and the civil versus the bestial, to hastily name a bunch of the subgenre’s mutating metaphors.

“Even a man who is pure in heart, and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms, and the autumn moon is bright.”

The Wolf Man

Off the bat 🦇 to aid you on this journey into werewolfery, I felt it was crucial to lay down the oft-contested lore. Confusingly, each individual werewolf picture tends to snatch certain rules from the established canon, and arbitrarily invent, or ridiculously eschew others—breakin’ the lore, if you will. Regarde.

- As prophesised by the Romani fortuneteller, Maleva, in Universal’s 1941 classic, The Wolf Man, “He who is bitten by a werewolf and lives becomes a werewolf himself.”

- If you have the misfortune of contracting a lycanthropic infection, you will turn into a werewolf upon the next full moon.

- Certain werewolves—some alphas, or direct descendants of an original bloodline, can willingly shape-shift whenever they desire.

- Lycanthropes are known to adopt the same shade of fur as their human counterpart’s hair.

- Werewolves typically have speedy, regenerative healing powers.

- Another way to break the curse is to kill the werewolf that bit you, and eat its heart—a rarely seen, and quite daft rule if you ask me.

- A familial lycanthropic bloodline is a potential cause. If yer dad’s a werewolf, you might be one, too. However, it can skip generations like male pattern baldness or something.

- A pentagram worn as an amulet can help break the spell.

- Lycanthropes are afraid of fire, which can kill them—makes sense.

- Werewolves aren’t keen on bright light—although it can repel, distract, disturb, or be used to get their attention, it doesn’t kill ’em, unlike vampires and Gremlins.

- Should you be murdered horribly by a werewolf, you will become a member of the living dead—trapped in an afterlife limbo until the offending lycanthrope is vanquished, the bloodline is severed, and the curse is lifted.

- The wolfsbane, or monkshood plant is a weapon against werewolves, weakening or killing them upon contact or ingestion. Peculiarly, in contrast, the effects can be reversed by using the ashes of the same type of wolfsbane that caused the poisoning.

- Serums, typically wielded by mad scientists, have been known to cause, stop, delay, control, or even cure werewolfism.

- When a werewolf dies, or the transformation period is over, the afflicted returns to a naked form as their clothes have been shredded, and likely discarded along the way somewhere. Some torn clothing may remain depending on the variable size of the monster—particularly if the werewolf is not enormous.

- A werewolf can only be killed with a silver bullet, a silver knife, or a cane with a silver handle.

- A werewolf can sometimes envisage a pentagram in the palm of the hand of their next victim.

- If you consume werewolf flesh, you too will bear the lupine curse, and transform at the next full moon.

I invariably prefer my selections to feel of the same ilk; the same era, too, if I can, with my previous picks all being late ’80s/early ’90s possession pictures, and this year’s all living together, and flowing on from one another as jocular, yet serious, or borderline contemplative representations of lycanthropic cinema, to provide an overview of the werewolf subgenre solely within what I feel is its most potent, culturally-impacting decade: the 1980s.

6pm

Three Little Pigs (1933) 8m

Before we go wild with decapitations and grotesque body horror, here’s a brief Silly Symphonies “Cartoon Club,” as QT’s New Bev revival house would call it, for any younglings wishing to participate in some gentle frights. Three Little Pigs is stronger than the The Big Bad Wolf in every way, but they go quite nicely as a pair, don’t they? Enjoy a musical memory lane double feature of 1930s piggy madness below for nish in glorious 4K.

“I’m a poor little sheep with no place to sleep. Please open the door and let me in.”

Big Bad Wolf, Three Little Pigs

6:10pm

The Big Bad Wolf (1934) 9m

“Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf?”

Pigs, The Big Bad Wolf

6:20pm

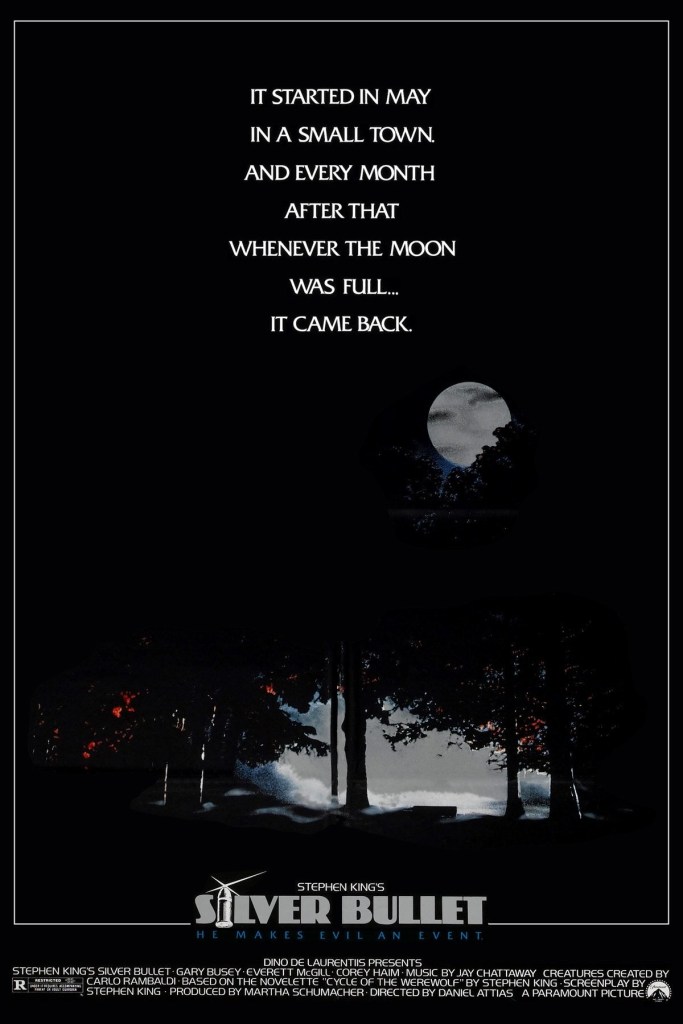

Silver Bullet (1985) 95m

“You ready? I feel like a virgin on prom night.”

Uncle Red, Silver Bullet

Silver Bullet, along with the second wave of ’80s werewolves, would satirise and skewer the social, political, and economic shifts of Ronald Reagan’s (the actor!?) time in office—the, lets face it, truism that seemingly harmonious groups shield scandalous secrets. Reagan’s policies were founded upon the principles of family, church, and community. King sinks his teeth into the patriarchal governments we’ve installed through the democratic process, and paints them as not only corrupt, but attests they actively pursue our destruction, with all social institutions—schools, marriages, and workplaces, each capable of descending into sick sideshows of self-serving rapacity, greed, and savagery.

The shapeshifting concept of the werewolf is ideal for exploring themes of evil masquerading as civil, and demonic disguised as human. Here, it’s wickedness lurking beneath the surface of idyllic, white Christian cliques in what has been coined “community horror.” At this point of the Eighties, there could very well be grotesque brutes, cannibals, or sadistic, murderous families in your neighbourhood. The Howling helmer, Joe Dante’s paranoia (or is it) picture, The ‘Burbs, along with the unforgettably slimy and satirical Society certainly expressed this, but it was perhaps David Lynch, who temptingly and skin-crawlingly articulated it best with the opening bits of Blue Velvet.

“Marty had read all the legends about werewolves, and though they differed on several minor points, they all agreed on one. It takes silver to kill a werewolf, and we were taking no chances.”

Older Jane, Silver Bullet

My initial reaction to 1985’s Silver Bullet was, God I wish this was better. I’d pencilled in Teen Wolf from the same year for my 6pm slot, thinking a gentler take on the lycanthrope would cater to younger audiences, and diversify my picks, but Fox and company didn’t pass my sensory test either—in spite of me making extensive notes on Rod Daniel’s retrospectively rich, satirical Reaganite capitalist skewering. I also seriously considered the original 1941 Lon Chaney Jr. picture, The Wolf Man, for its authenticity, brief runtime, and iconic status, but ’80s werewolves prevailed as they’re more provocative, wacky, watchable, and let’s face it, despite a recent deluge, neither before (unless you’re partial to the tamer originals), nor since (unless you have a real fondness for the early 2000s cluster of Ginger Snaps, Dog Soldiers, and the diminishing returns of the Underworld franchise), has there been a stronger run of werewolf pictures than the ’81-’85 period. The Howling, An American Werewolf in London, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, The Company of Wolves, Teen Wolf, and Silver Bullet stand as the meatiest of the mob, and intriguingly reveal a great deal about American life.

In his sort of extended dissertation thesis, Craig Ian Mann’s indisputable king of the werewolf movie books, Phases of the Moon—the preeminent literary analysis of werewolf cinema, Mann has a real bee in his bonnet about writers who solely see the lycanthrope as a mere Jekyll and Hyde parallel, and loathes the limitations of the “beast within,” dual personality character cop out, rampant in both film criticism, and audience readings alike. Longing for deeper work with added resonance, Mann posits the eras these pictures were produced reveal fascinating layers of subtextual meaning. I feel his frustration, particularly as so many post-Eighties werewolf films have been inadequate backward steps.

“What’s the matter, Bobby? You gonna make lemonade in your pants?”

Maggie Andrews, Silver Bullet

Some kinda monster is terrorising the town of Tarker’s Mills, Maine (surely among the most Stephen King settings ever put on celluloid). Typically, a werewolf is a tortured soul, and Silver Bullet’s villain’s purported mercy killings have an arguably altruistic motive—at least in the mind of its antagonist, as well as simultaneously feeling somewhat capricious and violent. Nevertheless, the slasher-esque whodunnit factor of Silver Bullet is a novel wrinkle, and kept me wondering for as long as it could realistically sustain. I won’t spoil who the wolfy culprit is here, because it’s a particularly enjoyable guessing game, and the only lycanthropic mystery of my three choices. Having said that, it’s evident on the cover of the Cannon VHS who the bad guy is, and it’s even painted on posters, so search them out at your peril.

“Hey, it’s Madman Marty on the Silver Bullet!”

Brady Kincaid, Silver Bullet

The director’s chair changed hands from Don Coscarelli (Phantasm, The Beastmaster, Bubba Ho-Tep) to the fresh outta film school, Dan Attias (AD on E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, second assistant director on Twilight Zone: The Movie and One from the Heart, and DGA trainee on Airplane!), although Coscarelli didn’t actually shoot a frame of the film—he didn’t even make it through preproduction. Silver Bullet’s slightly uneven approach and dual tone is likely due to the clashing of Dino De Laurentiis, who pushed for a hard R-rated picture, and Attias, who was angling for more of a kid-friendly PG-13.

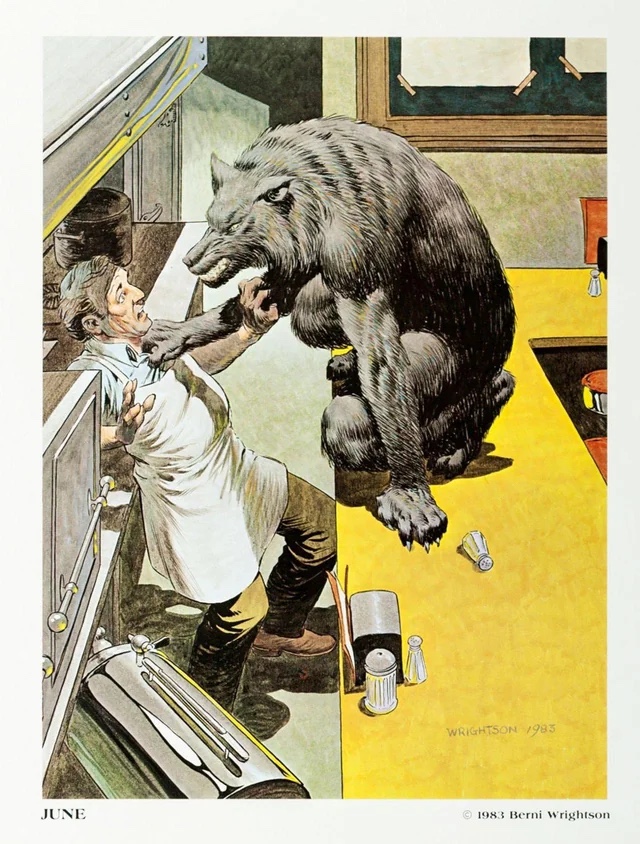

Silver Bullet’s originally hired—later fired helmer, Coscarelli’s shrewd take was to tackle the werewolf much like Spielberg’s recalcitrant shark, so the movie retains welcome remnants of that tried and tested approach scattered throughout. Silver Bullet boasts a somewhat bracing opening kill that’s largely unseen—but as with Jaws’s nude bather, Chrissie Watkins, the gory aftermath is. There’s a sparingly-shown child murder, with the parent of said youngster grilling the town’s cops about “private justice.” This vigilante-bating, angry mob haranguing goads the bar full o’drunken yahoos, who are all already chomping at the bit; eager to venture out as a pack, into tracking and hunting this beast down themselves. This Mrs Kintner-esque showdown, where a desperate dad puts a bounty on the beast’s head, is an unconcealed steal, and leads to a scene Coscarelli speculatively devised prior to his directorial departure—the passably suspenseful and visually appealing fog bank sequence, in which the avenging hunting party are waist-deep in thick mist, wading through a low-lying haze, and each get picked off one by one in a grisly manner. I have to emphasise the weakness of Silver Bullet is the werewolf itself. It’s far too bear-ish for my liking—however effectively hidden it is during Attias’s attempted Spielbergian set pieces. Talkin’ of Jaws-jackin’, there’s even a demise in a greenhouse, which resembles a shark attack as a bloke called Milt Sturmfuller gets dragged under the floorboards by the concealed creature.

“I’m a little too old to be playing The Hardy Boys meet Reverend Werewolf.”

Uncle Red, Silver Bullet

Silver Bullet depicts a white, middle class family with a preteen paraplegic son named Marty (Corey Haim). The dad’s around, but he’s palpably absent as well—somewhat distant and seemingly embarrassed by his son‘s disability. Here, Marty is wheelchair-bound. His fussy, put upon mother views him purely as a handicapped child who requires constant supervision, her nervous attention, and ongoing aid. Marty’s physical disability gives him a kind of superpower—an understanding and empathy for the werewolf-afflicted—almost as if he understands this suffering, and akin to the lycanthrope, must not give in to his own internal frustrations. Fun uncle, or “funcle” Gary Busey as Uncle Red has an affinity with Marty, and sees a reflection of his own alcoholic demons and deficiencies in his nephew, and they form a firm bond. Cue Busey dishing out WWF chair shots to the werewolf, getting hurled into mirrors and cabin furniture over and over, and reeling off throwaway improvisational lines about how he’s gonna open up a reptile farm and cook ’em on a barbecue.

“Holy jumped-up baldheaded Jesus palomina!”

Uncle Red, Silver Bullet

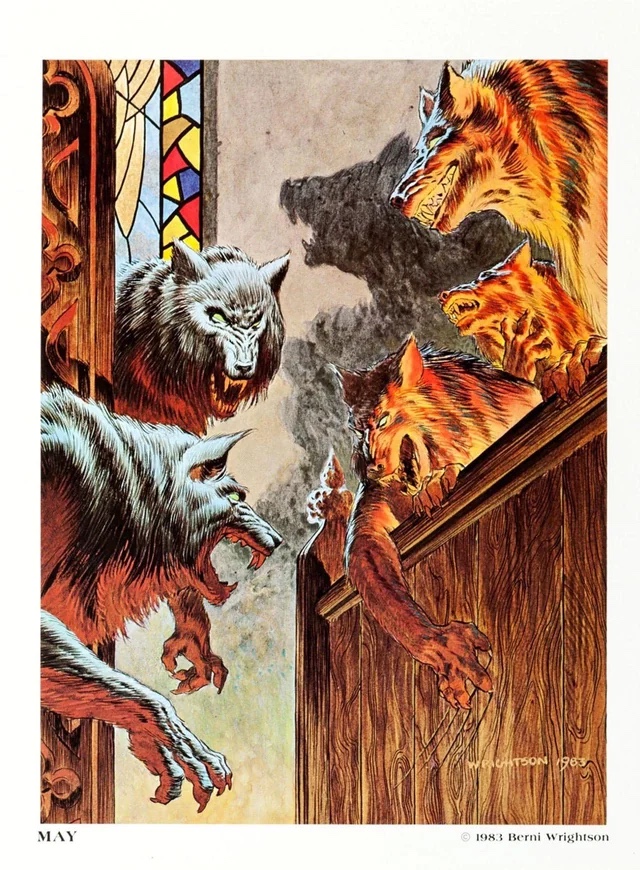

Far and away the finest sequence in the film—and a strong contender for best set piece in any of my picks, is the outstanding lycanthropic congregation fantasy in Silver Bullet. It’s one of those peculiar scenes where something’s clearly off, and we can’t quite pinpoint what it is. The ominous religious swaying with candles lit, the actors staring vehemently at Everett McGill as he sermonises, and every time we cut back to the uncanny parish, their wolf makeup is incrementally increasing. They’re getting hairier, and starier. Before long, they’re clutching at their own bodies, and their clothes are tearing away. Attias’s camera is juddering, the windows explode violently, and there’s blood everywhere. The stuffy organ music intensifies to a wild pitch with the strange performative smashing of the organ keys by a marionette-looking wolf woman. Then McGill is surrounded by furry hands, and bolts upright from his sweat-laden reverie.

Silver Bullet is available now on 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray from Shout Factory.

8pm

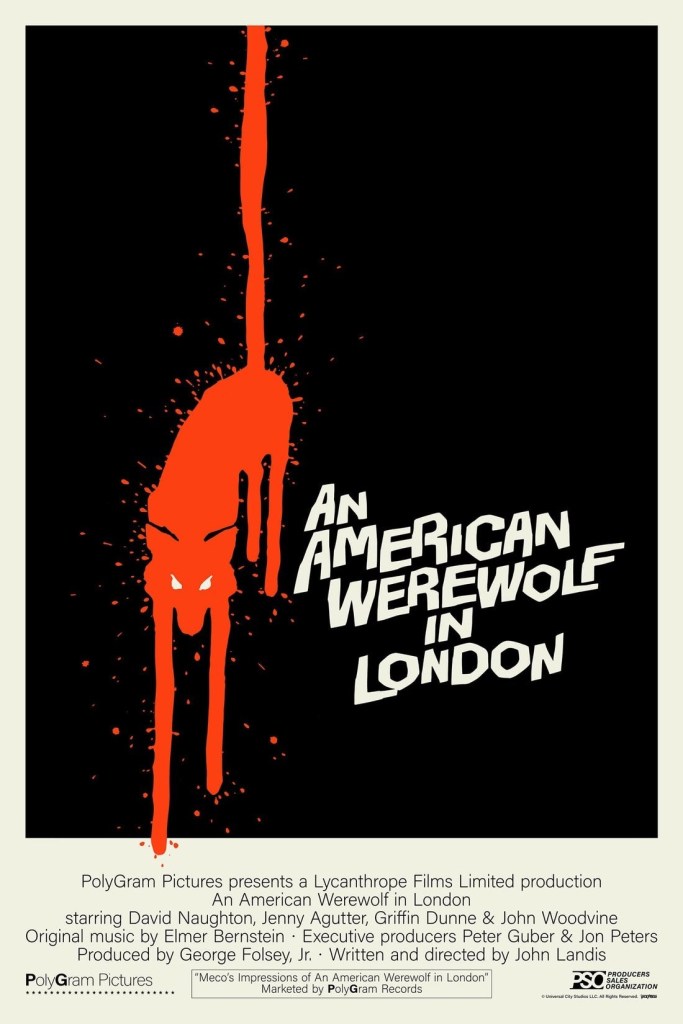

An American Werewolf in London (1981) 97m

“Winston Churchill was full of shit! Shakespeare’s French! Fuck! Shit! Cunt! Shit!”

David, An American Werewolf in London

I recall being disturbed by the menacing and intimidating VHS cover of An American Werewolf in London in my local video shop, Cav’s. That black box with understated purple text and blood-red 18 certificate, and a monster resembling greasy kebab meat. So much so, that I never reached for the top shelf, or plucked up the guts to audaciously point it out to my mum as a potentially sensible rental. For as long as a decade or so after that, I’d only seen its wildly-inferior, shockingly shite, 1997 sequel, An American Werewolf in Paris.

It wasn’t until 2007, prepping my MA graduation short, The Wilds, that my head of year, Nick Wright, suggested I seek out the Landis original as both films dealt with cryptid attacks in Northern England, and American Werewolf was clearly his go-to genre reference. My ten-minute short had absolutely nothing in the way of humour—although the Farmer protagonist wisecracking “Nine lives, my arse” like John McClane or Arnie might’ve let slip, was jokingly considered as a daft quip. However, I did pinch American Werewolf‘s painterly, neatly-composed opening establishing shots, but little else, as we were armed only with a dummy panther tail, and drastically under-crewed and underfunded for an ambitious creature effort—we did, however, shoot an actual deceased black calf from an abattoir with a 12 bore shotgun at 70fps hoping it would look acceptable. What I would’ve given for a panther-headed rug we could’ve turned into a rudimentary, hand-puppeted, big cat noggin for close-ups. My ace cinematographer, Adam Conlon, and I even momentarily contemplated the title, Blood of an Englishman—a direct quote from American Werewolf.

“Fe-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman.”

David, An American Werewolf in London

A handful of American Werewolf’s actors were treading the boards in Nicholas Nickleby at the time, and Landis judiciously plucked them from our revered Royal Shakespeare Company. You’ve also got the godlike genius, Rick Mayall, in an early, subdued role, and the preeminent cinematic Yorkshireman, Kes’s P.E. teacher, Brian Glover, at the same table, playing chess in the pub, and we wonder if that’s where the pair first became friends. Perhaps that’s the explanation for Glover’s madcap appearance as Richie and Eddie’s irate neighbour, Mr Rottweiler, in one of my favourite Bottom episodes, “Gas.”

The locals gawk at the two young yanks as they barge into the Slaughtered Lamb and eyeball them as if they’re from another world. They’re made to look like, and may as well be, astronauts to these village folk in this classic western saloon gag. The premise is somewhat of an echo of an early experience for Landis on the Kelly’s Heroes set where the upstart was working in an early role and experienced a Gypsy funeral and its unorthodox burial, which was superstitiously conducted to ensure a violent criminal’s corpse wouldn’t subsequently rise from its grave and cause further havoc. American Werewolf plays on an incredulous belief in legend, hokum, and claptrap, but muddles it with the smart, horror picture conceit that it all turns out to be shockingly true, and these smug, educated, seemingly advanced Americans fall foul of powers and supernatural workings they can never fully believe in or understand.

“You’d be surprised what horrors a man is capable of.”

Dr. Hirsch, An American Werewolf in London

1981 ushered in more practical, modern day werewolf tales, and introduced agonising mutations featuring distinctly lupine beasts—all gnashers and noses; hulking and monstrous. Transformationally-speaking, American Werewolf is the absolute pinnacle. Not even Rob Bottin’s real-time Howling shapeshift can compete with David’s agonised “burning up” transformation. The sudden, painful pang that strikes as he first begins to morph, followed by the terrifying, stretchy snout, and malleable-footed freak show in Jenny Agguter’s flat, that still churns the stomach almost 45 years later. At one point, David disturbingly reaches out to the camera lens as if he wants us, the audience, to help him, but we’re powerless.

“Beware the moon, lads.”

Chess Player, An American Werewolf in London

I definitely didn’t fall in love with American Werewolf instantly, and I must confess to finding the film clunky and clumsy in parts. I’m also not completely taken in by John Landis. The Twilight Zone tragedy and its weighty blame aside, I don’t believe I’d like to spend any time in his company. Having dinner with that bloke would be a real chore. Landis has an obnoxious, odious manner in interviews that I frequently find repellent. The “non-stop orgy” of the See You Next Wednesday segment heralds a revealingly sleazy tone born of the lascivious Landis just wanting Brenda Bristols to get her jugs out. He seems proud to be an arse. Landis has such an irksome, abrasive personality, and a crude, unfinished directing style that lacks subtlety. However, for a movie like American Werewolf, perhaps that’s precisely what was required.

“The supernatural, the power of darkness, it’s all true. The undead surround me. Have you ever talked to a corpse? It’s boring”

Jack, An American Werewolf in London

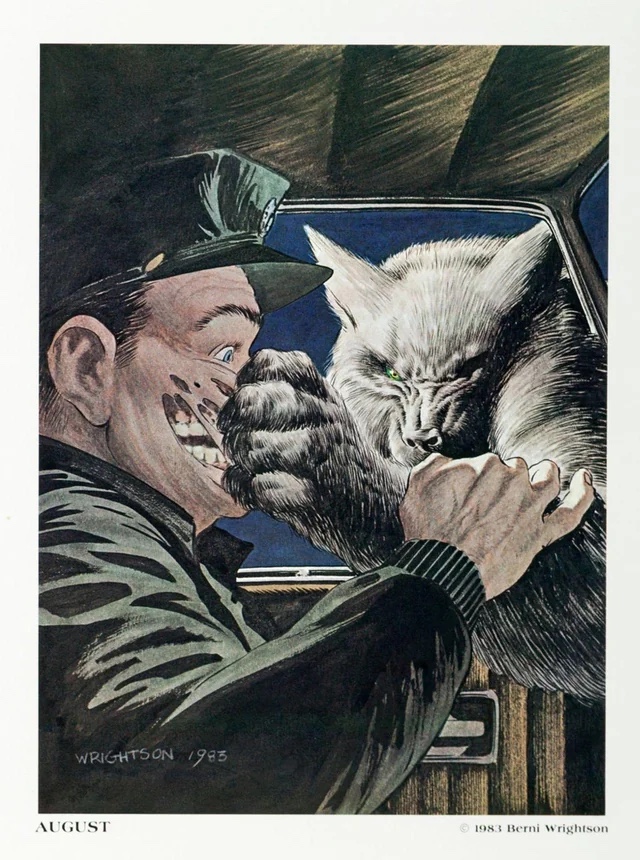

Early Eighties London seems so seedy, with jazz mags at newspaper stands, and adult cinemas adorning Piccadilly Circus. I do enjoy the peculiar interactions in the porno theatre. It’s unorthodox, funny, and dark, with the prolonged carnal moaning in the background juxtaposed throughout. The chirpy and courteous, yet fiendishly undead “Hello” couple basically invent Edgar Wright, and give birth to Shaun of the Dead’s entire comedic/horrific aesthetic with a single line of exquisitely delivered dialogue, and the three homeless fellas—Alf, Ted, and Joseph glint in the shadows of the cinema as they’re creepily cajoling David into topping himself. If you’re attuned to the cadence, “You must take your own life” even has audible shades of Shaun‘s Peter Serafinowicz.

Buses are spinning, drivers are in car crashes—getting hurled through their windscreens, and run over, lying bloody on the floor. Frantic pedestrians can only watch helplessly as Hieronymus Bosch chaos ensues. The wolf is loose—nipping at bystanders’ ankles. That head copper takes one in the jugular, and gets his head bitten off. It’s basically bumper cars in Leicester Square with a mad dog dashing about. It’s astonishing how little we glimpse the creature when it’s all broken down. We probably see more of the shark in Jaws, and that’s one of the reasons American Werewolf is still so effective. It’s not that you couldn’t do it now, it’s that there’s no restraint anymore. In a time where computer geekery can arguably accomplish anything, filmmakers opt to show everything. They can, so they do. They show their workings, and eliminate all mystique.

“I think that a werewolf can only be killed by someone who loves him.”

David, An American Werewolf in London

Like Roger Corman once said, “When the monster is dead, the movie is officially over.” American Werewolf’s wrap-up has little consideration for the audience. Granted, Agutter’s reaction is moving, and we feel for the gunned-down David, and accept the foregone conclusion of his werewolfery, but it feels like a disturbed double-decker with no brakes careering into a shopfront. American Werewolf’s clipped conclusion leaves viewers with a peculiar, unsorted feeling hanging in the air, and that’s partly why it’s my penultimate pick, as opposed to the final entry. Ebert didn’t jive with how suddenly Landis rolled his credits, and although I concede certain crowds prefer a softener, they, along with a chunk of critics, often mistake a blunt wrap up for a film devoid of professionalism. Tell that to Cronenberg’s The Fly, or the downbeat, sobering climax of Easy Rider, or the rapid, hard cut of Tobe Hooper’s original Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

“On the moors, we were attacked by a lycanthrope; a werewolf. I was murdered—an unnatural death, and now I walk the earth in limbo until the werewolf’s curse is lifted.”

Jack, An American Werewolf in London

A potentially profound video essay by Jon Spira on the Arrow 4K disc argues American Werewolf may hold a covert meaning. In Germany, the wolf is a brawny, indigenous, loyal protector as well as the name of a racist paramilitary group. The name “Adolf” means “noble wolf,” and Hitler would even refer to himself as such. His military headquarters in East Prussia was named, “The Wolf Lair.” The “Radio Werewolf” station was utilised by Nazi propaganda minister, Goebbels. “Wolf packs” were encouraged to hunt down enemies of the state. Curt Siodmak had been a successful novelist in Germany, and used The Wolf Man as a literary vehicle to explore his own wartime demons—where ordinarily decent men were turned into murderous animals. Siodmak laid out the werewolf lore that would follow for decades to come, and is cited and mimicked to this day. Many of Curt’s rules didn’t stem from folklore, he created them. Infectious bites, silver bullets, and tellingly, the pentagram forseen in the palm of a victim’s hand—those marked for death in Nazi Germany were forced to wear five-pointed yellow stars.

It’s worth wondering, is Landis wielding this loaded imagery, subtext, and historic context of the wolf to present a hairy, antisemitic Jewish allegory? David is a man in a country that doesn’t seem to want him, and drifts, disturbed by the murder of his best friend. The cheeky nurse’s subtle but perceptible, Eighties intolerance as she blurts out, “I think he’s a Jew” still lands palpably, suggesting some kind of surreptitious subterfuge. Is it an impudent throwaway (literally) foreskin quip, or an authorial hint at the public’s suspicion of the unrecognisably foreign—as sneaky wolves in sheep’s clothing?

An American Werewolf in London is available now on 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray from Arrow.

9:40pm

Michael Jackson’s Thriller (1983) 14m

“Darkness falls across the land. The midnight hour is close at hand. Creatures crawl in search of blood, to terrorize y’all’s neighbourhood. And whosoever shall be found without the soul for getting down must stand and face the hounds of hell, and rot inside a corpse’s shell.”

Vincent Price, Michael Jackson’s Thriller

What’s the first thing your mind conjures when Hallowe’en creeps around the autumnal corner? For me it’s either the song “Thriller,” or the iconic imagery from its 1983 companion promo. Despite Jacko’s Jesus juice-addled, baby-dangling plummet from grace, it remains the undisputed, greatest music video of all time, with no real contenders or pretenders to the throne. Yeah, it veers more into zombie territory, but it also arguably depicts one of the three, top-tier werewolf transformations of all-time, and certainly one of the most well known in pop culture. Iconic doesn’t even scratch the surface—record sales, the Thriller album cover, the audience views on MTV were through the roof. It’s a clear example of music and visuals interlocking so inseperably, and the art and the iconography being so momentous, that we can almost turn a blind eye to MJ’s alleged atrocities—for the 14-minute duration anyway.

“I’m not like other guys. I mean, I’m different.”

Michael, Michael Jackson’s Thriller

Thriller is a cornucopia of horror; a mashup packed with shout-outs to the hounds of hell, zombies, werewolves—or perhaps cat people, corpses, a haunted house, and showcases an alarming, foam rubber shapeshift—the werewolf, or arguably werecat here. It’s fairly feline, with prominent, extending whiskers, and memorably shows Michael in cat-like, yellow contact lenses. We’ve got spooky, mist-engulfed graveyards, cars breaking down, a grave emergence, Fred Astaire-inspired choreography, the sinister tones of Vincent Price, and a bassline that makes you wanna freaky deaky, right? Also, it boasts American Werewolf’s key crew of John Landis—who also made “Black or White” for MJ in 1991, cinematographer Robert Paynter, and Rick Baker’s special effects, which lead on perfectly from the previous picture. Stuff to spot for the sticklers and geeks—several makeup appliances were taken from American Werewolf and repurposed for the “Thriller” video, including the clawed hand appliance that extends over the porno cinema chair, which was reused on Jackson himself.

Say what you will about certified kook, Michael Jackson, and the controversy surrounding the bloke, but the magnitude of Thriller is undeniable, and the perfect example of an artist’s work transcending their problematic persona. If Jacko freaks you out, so be it! It’s Hallowe’en. What other night of the year would be more appropriate to be psychologically perturbed by the presence of Mike in your living room? All those disturbing claims and events aside, talk about commitment to the bit. Whatever you think of him, the devotion to the music, dedication to the video, the uncomfortable makeup appliances, and the art of it all is incontestable. It will endure; live, and last forever. Codswallop about a mere two nose jobs aside, MJ had a chilling physical transformation of his own—the vitiligo skin tone shift, an evident slew of surgeries—everything became altered as his career progressed, or perhaps deteriorated. Factor in the accusations during his life, and the damning Leaving Neverland revelations after his death, one could argue Michael became monstrous himself. I’d refer you to my piece on Captain EO and Moonwalker for an extended take on the nightmarish, poptastic clout of Jackson.

10pm

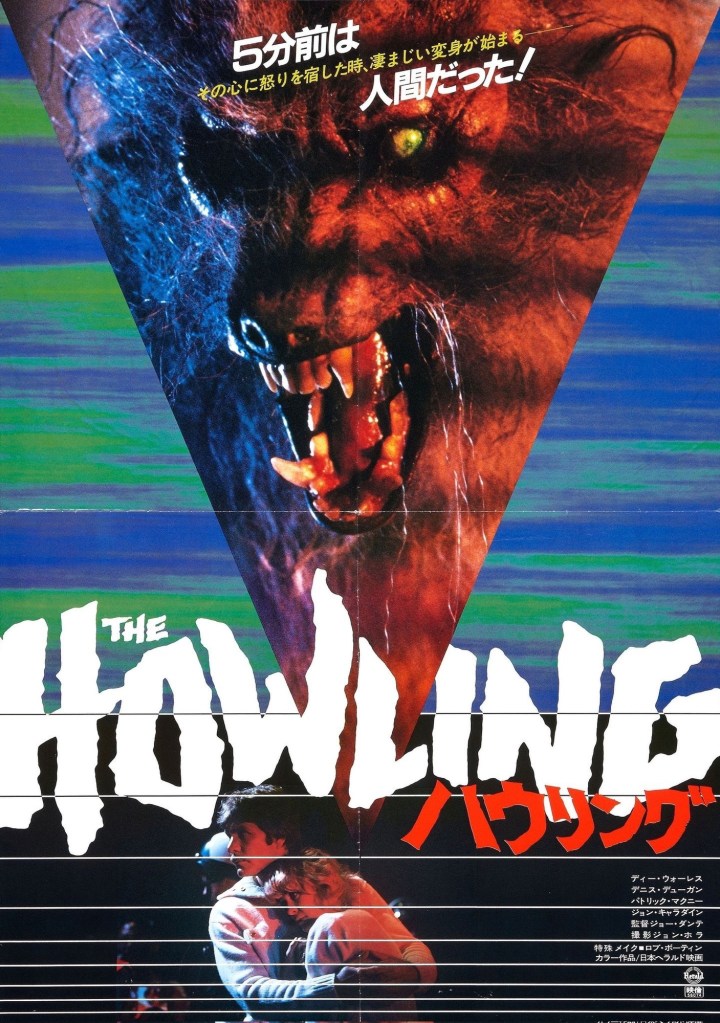

The Howling (1981) 91m

“What’s that werewolf movie with E.T.’s mom in it?”

Video Shop Girl, Scream

We’re off to Dick Miller’s lycanthrope lore bookstore for Joe Dante’s 1981 werewolf picture, The Howling—an identity-shifting story born of the original book’s writer, Gary Brandner, who stated, “We all have two faces: our public face, and our private face,” and revealed his motto, “It’s always, ‘Oh no, I’m a werewolf,’ or ‘Oh no, there’s a werewolf,’ but it’s never, ‘We’re all werewolves.'”

“You can’t tame what’s meant to be wild, doc. It just ain’t natural”.

Erle Kenton, The Howling

Intriguingly, The Howling’s werewolves are able to shift their shapes purely by choice, and their werewolfery is in no way linked to the lunar cycle, so their transformations are apparently allegorical of an embraced, alternative, lycanthropic lifestyle, and act as metaphors for any behaviour considered unsavoury by ’80s mainstream society. It’s condemning cultures that repress our natural urges, and simultaneously skewering quack psychotherapy as an ineffective form of oppression and control, whilst also targeting the exploitative extortion by the movement’s money-grubbing maharishis. The Howling has been latterly labelled as a parody of pop psychology, and the self-help gurus of the era. John Sayles—known for his subversive, satirical subtexts buried within the Piranha and Alligator screenplays, penned a picture that can be retroactively read as a fearful demonisation of sex—equating sexuality to monstrosity; a loss of control, where giving into carnal urges, erotic taboos, and indulging in intercourse outside of traditional marital relationships is sinful and depraved.

The Howling depicts a grotesque, almost sexually-transmitted werewolfery. The retreat where Dr George Waggner—namesake of the original Wolf Man director, does very little to help matters, with his colony’s cove-dwelling clients ultimately turning into serial killers, and insatiable nymphomaniacs. Again, the post-structuralists and subtextual film critics invariably have a field day with the Eighties, and love to leap to jejune conclusions, but the fact of the matter is 1981’s American Werewolf and The Howling were a smidge too early to consciously coincide with the advent of AIDS, or to make any intentional allusions to the human immunodeficiency virus. During the mid-to-late ’80s, particularly when it had anything to do with body horror, HIV was cited as an underlying theme. Most famously, the blood test paranoia of John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), and more speculatively, A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985), David Cronenberg’s re-imagining of The Fly (1986), The Lost Boys (1987), and The Blob (1988) remake. However, back in ’81, AIDS was not yet firmly in the public consciousness. Of course, in retrospect, many viewers saw these two movies during their video rental and VHS purchase era, which would have synched up with the panic precisely, and undoubtedly shaped perceptions.

“The things they do with special effects these days.”

Guy at Bar, The Howling

Long gone were the shoes and socks lap dissolves of Larry Talbot—played frustratingly, time and time again, by serial ham and cheese sandwich, Lon Chaney Jr, originally in 1941’s The Wolf Man with its contrived camera trickery and convenient cutting to illustrate a human shifting shape. As of 1981 we could see an elongating change-o-head snout stretching, rubbery feet elongating, and reverse hair sprouting. Not only could it now be achieved seamlessly on screen, but these two werewolfery depictions by the maestro; professorial master, Rick Baker’s An American Werewolf in London, and his protégé, the student understudy, Rob Bottin’s The Howling are two for the ages—they are, to this day, the duo to beat, and despite the advent of CGI, there’s no one, and nothing remotely close.

The Howling is an aptly suggestive take on the werewolf picture. As a warning, there’s a lot of chatter, and not a ton of action, but when we do get a transformation, it’s a prolonged, graphic, real-time indulgence. One could argue The Howling suffers from this excess as its pièce de résistance is a three-minute morphing sequence, in which Dee Wallace helplessly stands there petrified, and like us, witnesses the rubbery, lupine metamorphosis of Eddie Quist. It’s an unbelievable premise to have Karen simply stand there frozen; dumbfounded, glaring like an audience member while this all plays out. Granted, she’s petrified, mesmerised, or even hypnotised, but aside from the astounding effects, story-wise, the whole debacle adds up to very little, as Dee simply chucks acid in its face and flees. As illogical as this sounds, the scene still plays, and it’s impressive as hell. Dramatically speaking, this shapeshift seems somewhat stagey in comparison to American Werewolf’s private, pain-drenched transformation of David Kessler, which still tops my list.

Yet, some say it’s level-pegging between The Howling and American Werewolf. Pitting them against one another, The Howling scores points for its entirely in-camera bubbling rubber, and lumbering bipedal creature, and American Werewolf gets major props for its two and a half-minute metamorphosis, fully-lit under the fluorescent bulbs of Alex Price’s living room. In contrast, The Howling’s morph occurs partially veiled by its darkened, shadowy office setting. In my book, Rick takes the gross cake, although one could argue Baker’s protégé and student, Bottin’s practical skills surpassed his teacher’s with his show-stopping, breakdown-inducing, gooey, bladdery, pulsating practical effects work on The Thing the following year, and this could be a case of one artist spectacularly peaking as the other steadily climbs, and eventually passes their peer at the summit of a makeup effects mountain.

“Silver bullets or fire, that’s the only way to get rid of the damn things. They’re worse than cock-a-roaches.”

Bookstore Owner, The Howling

I responded to The Howling’s conceit that a media news team of investigative journalists; presenters, newsmen and women, and photographers are investigating this bizarre phenomena because they diligently read up on leads in a library, they record conversations, they do their research, and it was a diverting way of getting the exposition out. Dee Wallace is brilliantly expressive and empathetic as Karen White—a television anchorwoman, emotionally disturbed by frightening phone calls, and a risky undercover, faux-street walking encounter, in which she faced off with a murderous maniac.

White can’t conquer her amnesia, and only sees glimpses of the perpetrator in her dreams and visions, so her therapist, played nobly by Steed from The Avengers (no, not that one)—also Oasis’s chauffeur in the “Don’t Look Back in Anger” video, sends her to a retreat reserved for exclusive patients. Unbeknownst to Karen, she is soon drawn into a surreptitious, sexual subculture of werewolves, and must attend sorrowful, yet saucy soirées with beach barbecues, brazen hippy chicks, and folksy bluegrass-tinged makeouts. There’s some truly great moments of poignancy, with The Howling’s lycanthropes being so depressed that when we reach the cove, suicidal fogeys whinge about their old teeth before attempting suicide by bonfire. They’re completely over the idea. Even the werewolf therapist actively seeks to die by silver bullet, and attempts a suicide by cop—almost, leaving the rifle and silver bullet-toting Dennis Dugan no option but to quite literally “put him down,” vet-style.

“Silver bullets, my ass.”

Jerry Warren, The Howling

It’s not exactly on the nose (or snout), but we can palpably feel Dante’s reverence of, and references to the B movie genre fare he loves so much. The humour comes through in shrewd, self-aware flourishes like Dee Wallace sighing, “Hmmm” to herself before making the inevitable, dumb horror movie decision to investigate a strange noise. We feel privy to Karen’s brief indecision, followed by her scary movie character-indulgence. She might as well behave like she’s a girl in an Italian gialli, or an early slasher. Dante knows full well the only reason Dee’s doing it is because she’s in a werewolf picture—and because he knows, we also know—and because he wants us to know, we’re just as accepting of it as he is. I sensed Dante’s gaze during the scene; I felt him nudging my shoulder and throwing a wink, and it made me feel included as opposed to frustrated with such a tired trope.

“A secret society exists, and is living among all of us. They are neither people, nor animals, but something in-between.”

Karen White, The Howling

Although we do detect a few Gremlins-inspiring Pino Donaggio music cues during nightmare sequences, this is another world for Dante fans raised on his festive mogwai, Explorers, Innerspace, and The ’Burbs. We can, however, happily spot the Dante stable regulars—Robert Picardo (forever the Cowboy from Innerspace to me) as Quist, Kevin McCarthy as an acerbic newsroom producer, and last but not least, the immortal “that guy,” Dick Miller as a crotchety bookshop sage. By my calculations, Miller is the key to Joe’s trademark tone. As the Dante saying goes, “If there’s no scene for Dick, then why make the picture?” Levity inevitably finds its way in, with Bill hopping from vegetarian to carnivore the day after he’s bitten by a werewolf. It’s also a laugh spotting the Forrest J Ackerman (Famous Monsters of Filmland mags), Roger Corman (phone box man), and John Sayles (flippant coroner) cameos.

Originally, the climactic barn face-off was packed to the rafters with topless werewolf women, but Wallace had a limited nudity clause in her contract—which apparently applied to the movie as a whole, and alerted producer, Mike Finnell, who agreed it was gratuitous and vetoed the bosoms, declaring, “She’s right. It’s stupid. Put some clothes on.” Despite attempts to curb some exploitation elements, as with hairy-handed adolescent pleasures, there’s an intrinsic, lewd voyeurism to The Howling. It’s the sleaziest Joe Dante got, with an extended, explicit grindhouse depiction of a female rape—the victim naked and bound. Prolonged, graphic sexual torture is not what you’d expect from the director of Small Soldiers and Looney Tunes: Back in Action. This ain’t Gremlins 2: The New Batch. The Howling requires patience, and an open mind, but it’s brief, I believe highly significant, and delivered some of the finest werewolf imagery ever seen.

“”We have to warn people, Chris. We have to make them believe.”

Karen White, The Howling

As her last act of service as a human being, Karen boldly goes back on telly to unveil the secret werewolf society; warning the public, before sacrificially transforming live on air to convince any unbelievers—turning into the cutest she-wolf ever. Dugan knows he must kill her, and Dee knows it too. Although American Werewolf’s dark denouement is not without sentiment, and has a pathos of its own at the death, it can’t stack up to the way Dante’s film concludes. The Howling partly boasts a stronger ending because American Werewolf opted for an appropriately abrupt close—albeit with a lack of sophistication, irony, wit, or any global consequence of the story we’ve just witnessed. An American Werewolf in London bows out with a provocative and sudden conclusion—a real kick in the guts. In contrast, The Howling winds down in a much more satisfying, satirically sagacious and mischievous fashion. The Howling’s finale flits from heartbreaking sadness to all out body horror, and then a matter-of-fact, jet-black comedy before the credits appear. It’s a punch—powerful and poignant, with a humorous sting in the wolf’s tail; a chuckle-inducing coda with a deadpan bent to it, all the while resonating and reverberating in our minds as Dante’s rare hamburger patty sizzles through our recovering subconscious. It had to go last of my picks as there’s unquestionably no finer climax in werewolf cinema.

The Howling is available now on 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray from Shout Factory.

PS My This is Julycanthropy! playlist, which serves well as a HorrOctober of its own, can be found over at Letterboxd—31 werewolf films spanning time (like Vincent Gallo).

Carefully curated from our growing archive of Rewind Movie Podcast selections over the years, we also bring you our Letterboxd The Best of Hallore’ewind: Tricks + Treats 🍬 31 indispensable HalloRe’ewind go-tos to last you an entire HorrOctober! 🎃

The lunar cycle has come to an end, the airlock doors are shut for another year, and we must bid you a ghoulish goodbye. Feel free to travel back through the ages to our 2023 quadruple bills, Matt’s 2022 marathon essay, our exhaustive, inaugural 2020 iteration, and Devlin’s original 2018 all-dayer.

Until next time, Rewinders. Go now, and heaven help you.

Listen on Spotify

Listen on Apple Podcasts

Listen on Amazon Music

Listen on Deezer

Leave a comment